Much has been written about hip-hop’s recent takeover from rock as the most consumed music form in 2017, based on numbers released by Nielsen Music this month. There’ve been many reasons offered for this, including rock’s slower embracing of streaming technology and a reliance on old-school methods like concert revenues and physical and digital album ownership as its main sources of consumption.

Some have even addressed the state of current rock music, calling it “boring” while its constantly evolving hip-hop counterpart continues to excite the masses with young, brash and edgy artists who’ve cultivated an in-your-face, devil-may-care attitude that better reflects that of the millennial generation.

But nothing I’ve read has gone back to hip-hop’s origins and considered its recent crowning from the following, most ironic of perspectives.

Forty years ago this month, the Number One song in America was The Bee Gees’ disco smash “Stayin’ Alive.” That song’s immense popularity – along with the disco-drenched movie and soundtrack from which it came, Saturday Night Fever, helped catapult an already popular disco music genre from its more moderate success to astronomical levels almost overnight, causing a wave of otherwise uninterested artists to jump on disco’s bandwagon and further stoke its unprecedented commercial success.

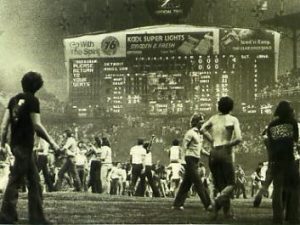

Eighteen months later on July 12, 1979, in one of the most embarrassing displays of hate-filled rage in American music history and with disco music reaching a boiling point in popularity, thousands of (mostly white and presumably straight) anti-disco revelers took to the field at a Chicago White Sox double-header baseball game in what was billed as “Disco Demolition Night” and burned (even exploded) as many disco records as they could bring into the former Comiskey Park in protest of the genre they somehow believed was a threat to rock music and/or their own lifestyles.

And so began a backlash that created a seismic shift in the popularity of a genre so ubiquitous that the first eight months of 1979 had seen disco owning 12 of that year’s first fourteen No. 1 singles on the Billboard Hot 100 (the other two were R&B-styled ballads by disco acts).

The underlying hatred of disco – a genre viewed as being enjoyed primarily by blacks and gay people – had actually been brewing for months, with radio stations hosting disco-free program segments and some switching from the genre altogether, despite its continued popularity and record-breaking sales levels. The anti-disco riot at Comiskey was merely the symbolic culmination of all the pent-up hostility (mostly in rock fans) that disco’s excesses had caused over the prior year or so.

As a result of the backlash and over the course of the next few years – prior to the release of Michael Jackson’s Thriller in late 1982 – disco in general but black dance and funk music in particular (which made up a large part of disco) took a huge commercial hit, with sales for black musicians backsliding to levels not seen since before the rock era began in 1955. Even non-disco-affiliated soul artists found it hard to recover in an industry whose reluctance to play and promote black musicians was as palpable as ever in disco’s wake.

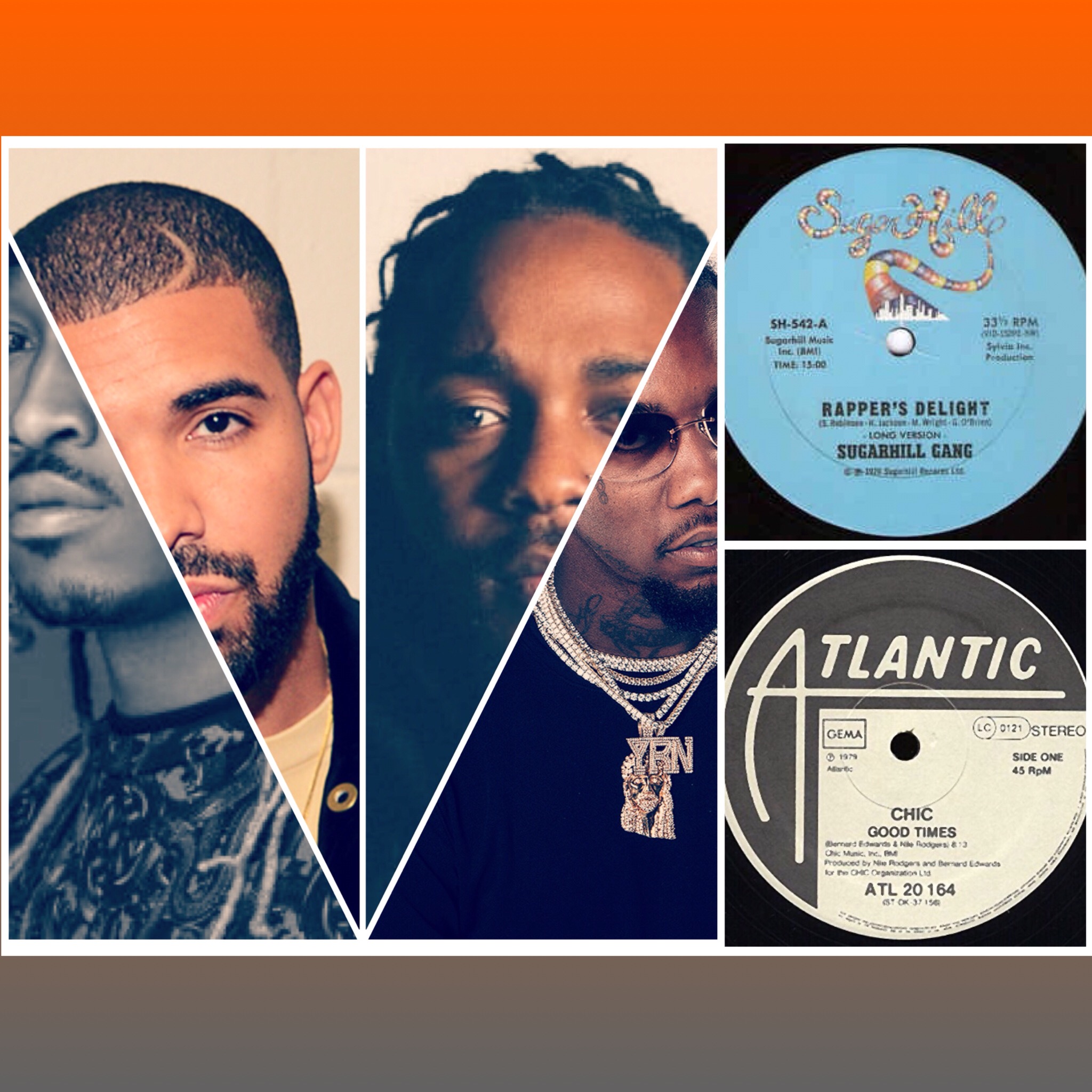

But disco – in an alliance with black funk music – had lit a tiny fuse before its untimely demise in 1979. And that fuse detonated towards the end of the decade in the form of a hip-hop record titled “Rapper’s Delight” by an unknown group out of Englewood, New Jersey called the Sugar Hill Gang.

Actually, rap music had lain in the trenches for a couple of years before “Rapper’s Delight” became the first of its kind to reach the pop top 40 in January 1980. Rappers, primarily in “rap parties” located in the Bronx, NY, had been free-styling over the backbeats and instrumental breaks of extended-mix disco and funk records before rap itself was ever committed to wax. Those uptempo records provided the perfect foundation for MCs who needed the time, the rhythm and the attitude that disco records offered to create the syncopated cadences that their craft demanded.

And, in a sense, rap was black kids’ answer to the call for a new and exciting music form to replace what disco and funk had been, except while disco music and the excessive lifestyles associated with it were extreme in their hedonism, rap provided a missing countercultural element, something that rock music had mostly mastered during its expansion in the 1960s and ‘70s.

Several well-known MCs emerged from that early NYC rap scene, but when the three guys who made up the Sugar Hill Gang stumbled upon one of the most iconic bass lines in what is largely considered the last Number One song of disco’s heyday, “Good Times” by Chic, and used it as the melody for their “Rapper’s Delight,” rap and hip-hop’s arrival became official…and it changed the course of music forever.

From the start, hip-hop music – then mostly performed and embraced by black youths in not-so-affluent neighborhoods – fought an uphill battle. It was shunned by mainstream music critics (and most parents) and criticized as a fad that would never last, just as its parent genre disco hadn’t. They believed it would either die an early death or continue to exist in marginalized communities where it would not become a threat to the Goliath that was rock music.

And for a long time, that narrative played out. During hip-hop’s first eight commercial years (1979-86) there were no rap albums that topped Billboard’s main chart, The Billboard 200. Not until 1987 did the first one happen, when Beastie Boys’ Licensed To Ill did the trick. It took even longer for rap’s first single to do it – Vanilla Ice’s “Ice Ice Baby” in 1990. (The irony that it took a group of white boys to do both is not lost on this writer, but I’ll return to that point later.)

For the next 30 years, hip-hop continued to develop and expand. It saw some setbacks but it also experienced several milestones and periods of huge growth. It’s had its own mini-eras, most notably the classic era of the late 1980s and the golden era of the ‘90s. It also has its warts – like the media-fueled East Coast vs. West-Coast feud of the ‘90s or the extreme nature of the often misogynistic, violent and vulgar lyrics that have gone hand in hand with its countercultural, if not narcissistic, attitude and messages.

But hip-hop has proven to be resilient through all the ups and downs, the good and the bad. It’s thrived on its own innovation and its ability to change with the times. That innovation has created many sub-genres and regional divisions, like gangsta, crunk, trap, east-coast, west-coast, southern and several others.

It even merged with other music forms – including R&B, rock and country – planting its seed in those genres along the way and creating hybridized rap-influenced versions of them that traditionalists and old heads can barely recognize or distinguish from rap itself. Popular millennial groups like twenty one pilots and Imagine Dragons make records that owe as much, if not more, to their hip-hop roots as their rock ones. (Note for the record, Wikipedia now lists nearly 100 musical acts that fall into the genre known as “rap rock.”)

And now in 2018 it’s official: last year hip-hop overtook rock as the most consumed genre for the first time in music history. Hip-hop owned eight of 2017’s ten biggest albums (which includes streaming numbers) and 17 of the 19 singles that were streamed more than half a billion times each last year.

It’s a development that’s been decades in the making. There’ve now been 172 hip-hop albums that have topped the Billboard 200 since “License To Ill,” including 63 this decade and 32 in just the past three years.

What’s ironic about all of this is that hip-hop could not have done it without the mainstream acceptance that it has received since 1987. Rap arguably has the Beastie Boys to thank for helping bring it into mainstream white households, much like white rock and roll artists did with black R&B songs in the 1950s.

Now it’s nothing to see or hear hip-hop used in ads, movies, sports references, Jeopardy questions (host Alex Trebek famously rapped the answers to a hip-hop inspired category last year) and in pop culture in general. Young white affluent consumers are as likely to have Migos, Cardi B or Lil Uzi Vert blaring from their headphones as is any poor young black kid.

Hip-hop has produced billionaire business moguls, record label owners, mega-record producers, and major tie-ins with popular consumer product brands (some of which owe their own success to that hip-hop synch). Had someone predicted this outcome in 1979, we would have all moved to have that person committed.

But hip-hop also could not have been No. 1 without rock music retreating in recent years. There’s been a seeming lack of excitement from the genre that ruled music for roughly six decades during what was generally known as the “Rock and Roll Era” or “Rock Era” for short. In essence, rock lost its edge over hip-hop when rock lost its edginess. Hip-hop picked up that baton years ago and has run with it ever since.

And now it is rock whose best new musicians likely exist in the trenches where smaller acts are still building their following on the local circuits.

Or it has been relegated to heritage artists in their sixties (or older) carrying its torch on the national front with high-grossing concert tours and occasional album releases. As data points, last year’s highest-ranked rock album on the Billboard year-end chart was by Metallica (at No. 12). Its highest grossing concert tour? U2’s “The Joshua Tree Tour.”

Both of those rock groups (as well as the album for which U2’s Tour was created) have been around for more than 30 years.

In music, “eras” are usually defined as the period in which one music genre has had dominion over all other forms, mainly commercially but culturally as well.

It’s hard to pinpoint exactly when the rock era ended (or if it really has) and the hip-hop era began, but given that music historians have never defined any earlier periods in modern music as belonging to multiple eras simultaneously, many are beginning to acknowledge that we are firmly entrenched in the hip-hop era, no longer the rock era.

Whether one fully subscribes to this likely depends on where One falls on the rap-sucks spectrum. Just like disco before it, hip-hop’s haters will cite rap’s most visible warts as reasons to categorically despise the genre (usually ignorantly without exception) while attempting to keep subtle elements of race and culture out of the discussion.

Assuming we are singularly in the hip-hop era, the question that then remains is, when did this era actually begin?

For the rock era it was easy to define its beginnings. Most agree there was a critical moment in history that marked the start of the rock era in 1955. It was generally seen as when the song “Rock Around The Clock” by Bill Haley hit No. 1 and rock and roll acts like Elvis Presley and Buddy Holly soon followed.

For hip-hop, finding a specific moment to mark the beginning of “the hip-hop era” is not that simple. It didn’t happen overnight or with one seminal moment. Did it began in 1987 with that first No. 1 album by the Beasties? Or maybe it happened three years later with the emergence of MC Hammer’s Please Hammer Don’t Hurt ‘Em, still the longest-running No. 1 album by a rapper in chart history, or maybe it was later in the 1990s when several iconic MCs (Tupac, Biggie, Jay-Z, Nas, Eminem) emerged and have since been regarded as perhaps the greatest rappers of all time.

Whenever it was, one thing is certain: the hip-hop era might not have happened had it not been for those disco records that provided the back beat and the backbone for so many hip-hop artists who pioneered rap and paved the way for what it has become today.

Unlike its disco forefather however, it’s unlikely that a “rap sucks” campaign could ever have the devastating effect on hip-hop that the disco sucks campaign had on disco nearly 40 years ago. Too many years have passed and rap is now fully engrained in international culture.

To borrow the title from that Number One disco record from 40 years ago, hip-hop is most definitely “Stayin’ Alive.”

And in that way, these are the “Good Times” for rap music, and the “hip-hop era” of today could be here to stay.

And that, my friends, would be disco’s ultimate revenge.

DJRob

I’m a black man I hope to heaven that rap and hip-hop culture dies and soul, blues, jazz, disco and good black music comes back to prominence,