Twenty years after his death, we still need Tupac in this world – even more so now.

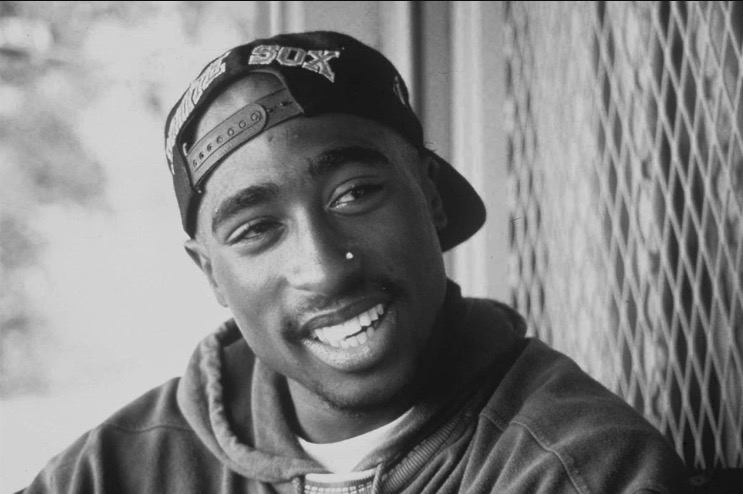

Rapper Tupac Amaru Shakur (a/k/a 2Pac) lived for just 25 years. We knew him for only five of those. His life ended 20 years ago this week on September 13, 1996, six days after being gunned down in a drive-by while riding in Las Vegas, NV.

As so many music and cultural historians will do on this milestone anniversary, djrobblog takes a look back at the legendary artist’s era, his impact, his demise and legacy…and why we still need him today.

His Era.

At the time of Shakur’s untimely death, hip-hop was on a commercial and creative trajectory unlike ever before in its then nearly 20-year history. Rap artists in the 1990s were regularly selling millions of albums, topping the mainstream pop and R&B charts with ease, and – perhaps most notably – doing all of this while embracing some of the very ideologies that mainstream America had previously feared or held in the highest contempt. Sure you had pop-friendly artists like MC Hammer, LL Cool J, Kris Kross and others making their mark with innocent, candy-coated rap tunes about girls and romance, partying and drinking, and – in Hammer’s case – movie/TV characters like the Addams Family.

But right alongside those confectioners were two forms of rap’s counterculture that couldn’t be more blatant in their accounting of black life in America. On the one hand, you had socially conscious rappers whose main goals were to awaken the black community, instill a sense of responsibility in its members and hold America accountable for its oppression of the people in that community.

On the other hand you had rappers who gave gut-wrenching tales of street battles, dope-peddling and loose women (who were “affectionately” relegated to being “bitches,” “hoochies” and “hoes” by many of rap’s protagonists). These artists were often unrelenting in their approach, simultaneously embracing the protest spirit and social activism championed by their ancestors while embodying the misogyny and “gangsta” culture that would come to be associated with their hip-hop descendants for the next 20 years – for better or worse.

Yet, for better or worse, ’90s hip-hop was the genre’s most expansive period – and arguably its best – both from a creative standpoint and a financial one. It was the subtext in the larger story of a music industry that, as a whole, was experiencing its most financially lucrative years ever. And, for the first time, rappers were getting a chunk of that pie with mega-selling albums on par with their rock, country and pop music counterparts…in some cases exceeding them.

Just look at some of the names that emerged during the 1990s. It reads like a Who’s Who in Hip-Hop with a roster including Jay-Z, Nas, Common, The Roots, A Tribe Called Quest, the Fugees, Outkast, Lauryn Hill, Scarface, Wu-Tang Clan, Mobb Deep, Cypress Hill, Snoop Dogg, and Lil Kim, among many others.

It was also the decade of Tupac (2Pac) and The Notorious B.I.G., two rappers who, despite their relatively short lives and famous rivalry, left indelible marks that still rank them among hip-hop’s all-time greatest on many experts’ lists. Those two rappers became the faces of mid-’90s hip-hop and beyond. Unfortunately, they were also the commanding officers in hip-hop’s bogus civil war between America’s two coasts: East and West, which I’ll get to in a moment.

His Impact.

Tupac, who was born in East Harlem, NY, in June 1971, had the benefit of three factors in his career: excellent timing (the 1990s), great perspective (from his upbringing), and a compelling rap flow that was uniquely his.

The timing was a function of when he came of age, a thing he couldn’t control but one of which he certainly took advantage. On hip-hop’s timeline, he came after Ice T, Boogie Down Productions, N.W.A. and Public Enemy, so the stage had already been set for mainstream consumption of the brand of hip-hop ‘Pac would be pushing: hard-hitting, sometimes menacing, often troubling street tales that gave America unique insights into its darkest corners from an insider’s perspective. And the world was ready for more of it.

Tupac’s perspective was likely developed through his upbringing, which included exposure at an impressionable age to many people who were instrumental in championing black causes. His mother, Afeni Shakur, and several men in his life were members of the Black Panther Party, a revolutionary but controversial socialist group whose extremes ranged from organizing community social programs for underprivileged children to violent engagements with police in its quest to liberate blacks from the oppression that was (and unfortunately still is) present.

The flow? Well, that was all 2Pac’s. Before he arrived, no one had heard anything quite like him. His alliteration went beyond the standard repeating of rhymes with the same syntax at a constant pace over sixteen bars, as had been the case during much of hip-hop’s earlier years. Instead, his phrasing mixed word elongation with unexpected holds and pausing, an infusion of melody at times, and clever vocal inflections to drive his points home.

All of this resulted in his first two albums, 2Pacalypse Now and Strictly For My N.I.G.G.A.Z… becoming instant classics with hardcore street tales and a poetic flow unlike any we’d heard before. On top of his other features, those albums invoked 2Pac’s unique story-telling style that would influence many future rappers, including his former friend and ultimate nemesis, Biggie.

As his popularity grew, in part due to his appearance in films like Poetic Justice and Menace To Society, more and more people wanted to hear what the poetic artist had to say. And he often would oblige by having more and more to say – about anything – both on and off-record.

On record, we began to get insights into just how complex and conflicted the rapper truly was. In 1995, he released his third album, Me Against The World, one that was considered his magnum opus at the time. The album revealed a sensitive man capable of celebrating the women he loved (his own mother in “Dear Mama” and a romantic interest in “Can U Get Away”).

Yet it also showed a vulnerable side, as he contemplated his own life’s value in tunes like “If I Die 2Nite” and “Lord Knows.” Me Against The World captured the anger of an artist who’d seen a lot in his 22 short years (at the time). To wit, where N.W.A. had only challenged authority with their now-famous “F— Tha Police,” 2Pac took it many steps further and left no one free from his wrath in “F— The World.”

The album famously débuted at #1 on the Billboard album charts while Shakur was incarcerated – the result of a sexual assault charge – becoming the first album of any type with that distinction.

It was, however, on those last albums during his lifetime (Me Against and later All Eyez On Me) where the messages became more muddled. Tupac increasingly seemed less concerned with the plight of black America and his own vulnerability and more interested thematically with the exploitation of those things. The streets’ greatest poet more and more replaced philanthropy with misogyny. This, too, is when his albums’ sales exploded (unsurprisingly), culminating with his most successful commercial release: 1996’s All Eyez On Me, the first part of his West Coast deal with Death Row Records.

That West Coast deal (His Demise).

It’s easy to forget Tupac’s alliance with the West Coast only lasted eleven months, beginning in October 1995 upon his release from the brief stint in prison (with bail posted by Suge Knight as part of a record deal). It was a partnership on which Tupac would stake his life, but it was also a dubious connection, with ‘Pac joining Knight’s Death Row Records only after the former east-coast rapper believed that people in Bad Boy Entertainment’s New York-based camp (helmed by Sean Combs and including Biggie among others) were involved in an earlier attempt on his life.

It’s then ironic and strangely poetic that his newer alliance proved to be the fatal one, with ‘Pac’s murder occurring under Suge’s watch after the two had attended a Mike Tyson fight in Las Vegas.

And with his death – and later that of Biggie – rap’s most-hyped, yet silliest civil war (the East Coast-vs-West Coast rap farce) came to an abrupt end. Both rappers’ lives would be extinguished within six months of each other, with their assassinations marking the culmination of what had been the hip-hop era’s dumbest internal conflict. Its two most prominent mouthpieces were wiped out, leaving in their wake an eerie silence that revealed just how contrived and bogus the East-vs-West thing really was.

His Legacy.

But Shakur’s death did more than end that battle, it silenced a voice that had been so outspoken on matters affecting the black community, with rap stories told from the perspective of one of its own who’d been both hardened by society’s ills and reared by ancestors who devoted their lives to fighting them.

It was a voice shaped by internal conflict, at times self-promoting, at others introspective. At times violent and sadistic, at others aware of his own mortality.

But his was always a clear voice, a coherent one during challenging times with a central egalitarian theme running through it during an era when hip-hop’s impact was being felt the most. What better time than the early to mid 1990s to deliver the messages that Tupac wanted to be heard, a time when people were hungrier for (and more curious about) hip-hop and its purveyors than ever before. A time when hip-hop was also at its most impressionable.

It’s a voice we still need twenty years later.

Don’t get me wrong, it isn’t that hip-hop as a genre died with Tupac (or Biggie, for that matter). Rap music still thrives in the 21st century, at least commercially. In fact, during 2015, it was one of only a few genres to actually experience an increase in sales revenue over the previous year, with ten of rap’s albums reaching Number One last year. Over 130 such albums have hit #1 on Billboard’s main album chart in the 20 years since 2Pac’s death, vs only 20 albums in the seventeen years of rap’s commercial existence before then.

No, what hip-hop needs today is a “voice” or a “face,” a new larger-than-life figure who both captivates and motivates. One who transcends the genre and the music itself.

There are few candidates out there, but are they worthy?

Kanye could be that voice, he certainly transcends the genre. But he is oftentimes incoherent, and he could hardly be seen as the street’s pied piper – like 2Pac was – instead choosing to mate with the likes of a Kardashian and wage war with pop stars like Taylor Swift. His battles often feel white-collar and elitist compared to the blue-collar wars that 2Pac waged.

Drake might be that voice – he’s certainly enjoying the most chart success these days. Problem is, the same issues that plagued America (and Tupac Shakur) in the 1990s still exist – perhaps even more so now than before. An artist like Drake, who hails from Toronto, Ontario and has mixed it up with fellow Canadian and pop heart-throb Justin Bieber, doesn’t have the kind of street cred that ‘Pac did (heck, Drake’s own songwriting has come into question in recent years). So expecting him to deliver serious messages on behalf of a downtrodden and oppressed community – and do so with believable authority – is expecting a little too much.

Big-name rappers like Future and Big Sean are more like the Master P’s and Busta Rhymes of 2Pac’s era – popular big sellers, yes. Streetwise, perhaps. But they’re more like also-rans now who certainly are not viewed as the hero that Shakur was. These rappers – especially Future – instead embrace inarticulations and indifference in their music. Incoherent mumble rap and egocentricity have replaced clarity and concern. When you actually can understand them, rarely do today’s rappers look beyond self-gratification in their tales of exploits with money, women and cars.

While that subject matter is nothing new in hip-hop (it certainly existed in 2Pac’s and Biggie’s era), it was at least balanced by those rapper’s abilities to tell streetwise tales of the perils of such lifestyles while also seeking to uplift the community when it was needed the most, particularly in ‘Pac’s case. Today’s biggest-selling rappers either haven’t lived the pain or are unable to recreate it on tape. Yes, a few rappers have grabbed recent headlines and spoken in opposition of police brutality and social injustice from time to time, but few, if any, carry a voice as loud and as beckoning as Tupac’s was.

Maybe Kendrick or J. Cole will be that face or voice. They’re often cited as being among the more socially conscious rappers out there. Maybe Kendrick already is and we just don’t realize it yet because we’re living in his moment now.

You know how they say you don’t really appreciate the era in which you live until it’s gone?

Well, that doesn’t apply in Tupac’s case. We knew about him then what we still know now. Sure, Tupac Shakur wasn’t innocent of the misogyny, self-promotion and f–k-the-world attitude of which I’ve already spoken. He was guilty as charged, particularly during the last year of his life.

But he was so much more than that. He left to hip-hop multiple legacies in his wake. He was both poet and perpetrator. During his life, he simultaneously satisfied our hunger for consciousness and our thirst for ratchetness. With few exceptions, rappers in the two decades since have run with the latter and forsaken the former.

It’s what record company conglomerates want and it’s what they think we want (or they’ve conditioned us to want).

If Tupac is partly to blame, we need him now to come back and correct the record…for hip-hop’s sake and ours.

But that won’t be happening, and, in the meantime, as 2Pac once said, “Life Goes On.”

Continue resting in peace, Tupac Amaru Shakur.

DJRob

An extra piece of 2Pac trivia: Tupac Shakur has five Number One albums to his credit (two before he died, three after; one credited to Makaveli). To see djrobblog’s up-to-date list of all the rap albums that have ever reached #1 on the main Billboard album chart – The Billboard 200 – including Tupac’s, click here.

Succinct and your style of writing? Amazing

Thank you so much!