(October 28, 2021). As I write this, I realize that what passed as acceptable in comedy during the 1970s would not necessarily fly in today’s more politically correct and woke environment, and perhaps appropriately so.

Still it’s interesting to discover the extent to which some art tested the boundaries of cultural offensiveness back in the day and, in some cases, even more astounding to discover who took part in its creation.

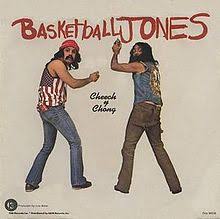

Take, for instance, the song “Basketball Jones,” a 1973 parody tune by legendary stoner comedians Richard “Cheech” Marin and Tommy Chong. I was reintroduced to this slice of juvenile banality during a recent re-airing of a classic episode of “American Top 40 with Casey Kasem” from September 29, 1973. It was an amazing countdown featuring some of the best-known pop classics (and a bunch of great soul ones too) by many of the biggest stars of the early 1970s.

When the legendary host Kasem arrived at the week’s highest new entry at No. 26, he gave a brief intro to the song, including some information about its two principle artists—comedians Cheech and Chong—and then played their latest hit: “Basketball Jones.”

“Basketball Jones,” which went on to climb as high as No. 15, mocked an earlier soul classic called “Love Jones” by a young Black group out of Chi-town named Brighter Side of Darkness. They were a quartet of three guys just out of high school plus a 12-year-old lead singer named Darryl Lamont. They were one-hit wonders but that lone hit was a biggie, as sleepers go. “Love Jones,” after entering the charts in the fall of 1972, became a No. 3 soul smash at the beginning of 1973. It also crossed over and became a No. 16 pop hit that February.

“Love Jones” was a ballad in the true vein of early ‘70s soul jams. It incorporated a spoken-word lyric—or rap—delivered in as sad a cadence as one could muster from the perspective of a teenager about his obsession with a girl in his class. The term “jones” was common slang for addiction, and the young fella’s love jones in this case was so strong it was “almost like that of a junky’s.” On repeat listenings, this “Jones” may sound campy now, but in 1973 it was a serious matter…one to which many a soul brother (or sister) could relate.

In the parody song several months later, Cheech Marin portrays the character Tyrone (as in “tie your own,” and the name speaks for itself) Shoelaces. He sings the lyrics to “Basketball Jones” in an intentionally bad falsetto, mocking a vocal style that was common—just not the bad part—among Black soul groups of the day, including the Chi-Lites, the Dramatics, the Stylistics, and so many others. Except, in this case, not only does Cheech sing in falsetto, he also raps the spoken-word lyrics in that same awful tone (Note: none of the Black musicians who sang that way also spoke in falsetto, one of the many exaggerations the two comedians employed “for effect”).

The singing—including some hilariously off-key backing vocals by his female “cheerleaders” and other vocalists—was offensive enough. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Check out these lyrics from “Tyrone,” presumably a Black character, about his obsession with basketball:

“Yes, I am the victim of a basketball jones. Ever since I was a little baby, I always be dribbling…One day, my mama bought me a basketball, and I loved that basketball. That basketball was like a basketball to me. I even put that basketball underneath my pillow, maybe that’s why I can’t sleep at night.

“I need help ladies and gentlemens,” Cheech continues in his worst ethnic dialect. “I need someone to stand beside me. I need someone to set a pick for me at the free throw line of life, someone I could pass to. Someone to hit the open man on the give-and-go, and not end up in the popcorn machine. So cheerleaders, help me out!”

“Basketball Jones, I got a basketball jones, I got a basketball jones oh baby ooh-oo-ooh!,” the cheerleaders follow and repeat in unison.

Clever use of sports metaphors aside—and, admittedly some of them were clever…I mean, where else would you find basketball phrases like “setting a pick” or “give-and-go” in describing one’s craving for affection—the racial stereotypes here are so blatant that a kindergartner could pick up on them.

Cheech remains in his “Tyrone” character throughout the song’s four cringeworthy minutes, ad-libbing lame one-liners (“yeah, I could dunk it with my nose”) in agonizing falsetto while the chorus unrelentingly builds around him (and unfortunately doesn’t drown him out completely). It wouldn’t be surprising to learn that more than a few doobies were passed around in the studio that day while he and Chong perpetuated stereotype after ethnic stereotype with their horribly sung brand of humor.

The real surprise, though—besides the fact that “Basketball Jones” actually outperformed its source song on the Billboard Hot 100 by one position—is who was in the studio with Cheech and Chong that day as they laid down those tracks. The list of reputable artists who played on their “Jones” reads like a Who’s Who of session musicians, legendary singer/songwriters, and Rock and Roll Hall of Famers (including two double-inductees).

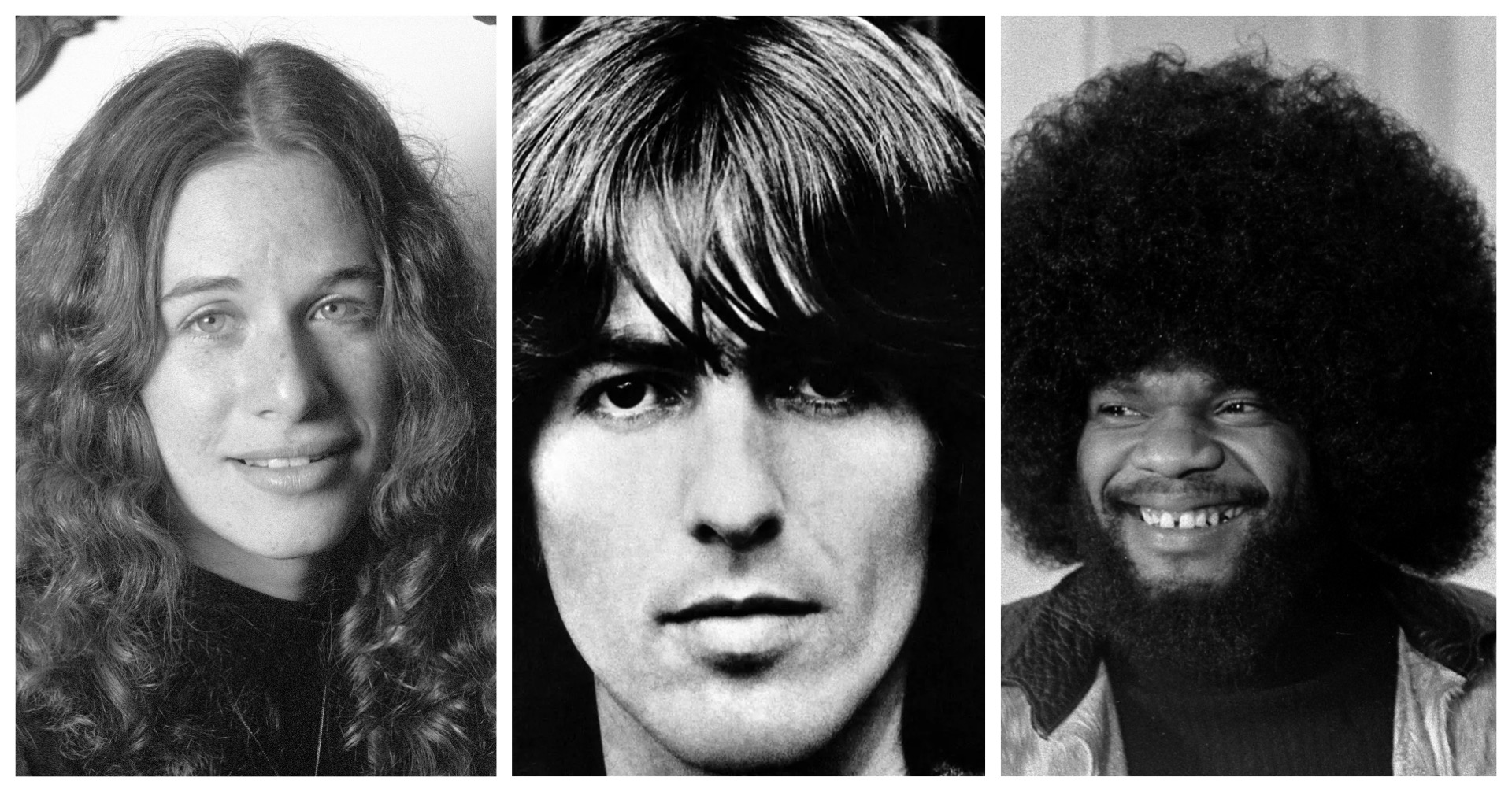

Consider these names: George Harrison, Carole King, Billy Preston, Darlene Love, Michelle Phillips, and Ronnie Spector. All of those notable singers/musicians and more were in the studio during the recording of “Jones” and all of them had prominent roles in the song’s creation.

Harrison played electric guitar on the novelty song, King was on electric piano, while Preston played organ. Harrison’s guitar can be heard prominently throughout.

Legendary singers Darlene Love, Michelle Phillips (of the Mamas & the Papas) and Ronnie Spector were joined by two of Love’s former group mates from the ‘60s group the Blossoms—Fanita James and Jean Kings—in the role of “the Chearleaders” (or backing vocalists) on “Jones.”

Other notable contributors included Klaus Voormann, German producer and musician who also played bass for Manfred Mann (also “The Mighty Quinn” flautist), Nicky Hopkins (session musician for The Rolling Stones, The Who and The Kinks), and Jim Keltner, famed session drummer who played on John Lennon’s early ‘70s solo albums and Bob Dylan’s “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door.”

How important and respected were these musicians in the industry?

Well first there’s Harrison, a two-time RRHOF inductee who had earlier that summer reached No. 1 with the wistful ballad “Give Me Love (Give Me Peace on Earth),” this after having had earlier success with his famous humanitarian Concert for Bangladesh album and the 1970 classic All Things Must Pass featuring his first No. 1 solo hit, “My Sweet Lord.” Oh, and did I mention he was once a Beatle?

Then there’s Billy Preston, long considered the fifth Beatle, who had also hit No. 1 that summer (his “Will It Go ‘Round In Circles” displaced Harrison’s “Give Me Love” at the top). Preston was a highly respected keyboardist who had famously played with the Beatles and was in the midst of a hugely successful singing career. He would rack up four gold top-five singles, including two No. 1s, before the decade was halfway over.

And, of course, there’s legendary singer/songwriter Carole King, another double RRHOF inductee who had released the classic Tapestry—at the time the biggest-selling album by a female—just two years earlier. She was also in the midst of a highly successful singing career after having written some of the biggest hits of the 1960s and early 1970s for other people.

Michelle Phillips, Ronnie Spector and Darlene Love each had major success in the 1960s, with each one continuing to be relevant in the ensuing decades. The resumes of the other session musicians noted above speak for themselves.

So how was it that this rock “supergroup” of highly respected and accomplished musicians came to play on “Basketball Jones,” one of the more offensively bad parody singles of the 1970s?

First we must consider the label on which “Basketball Jones” appeared. Ode Records, to which Cheech and Chong were signed, was also the home of Carole King. Ode was founded by legendary producer Lou Adler, who has been credited with discovering C&C, and who owns production credits on their “Jones.”

Ode was distributed by A&M Records in 1973, and much of their material was recorded in the A&M studios. That likely explains the presence of artists like A&M’s Billy Preston and, by association, best pal George Harrison.

Adler, according to a booklet accompanying Cheech and Chong’s compilation album Where There’s Smoke, There’s Cheech and Chong, recalls phoning Carole King to have her join in the “Basketball” session, while many of the other musicians were in A&M studios “doing different projects.” Adler referred to the collaboration as a “wild session” where music was “spilling out of the studio into the corridors.”

The result was “Basketball Jones,” that rare case of a novelty record (No. 15 peak) outperforming the song it parodied (No. 16) on the charts; a song so badly done it was funny, or at least it was considered so nearly 50 years ago.

Cheech and Chong would follow “Jones” with the top-10 hit “Earache My Eye,” another comedy record that referenced basketball in its lyrics but was more notable for its guitar riffs and the “disciplinary” dialogue between “father and son” at the end. That record, ironically, created more controversy than its predecessor, and peaked even higher on the chart (a No. 9 Hot 100 hit in 1974). In retrospect, “Earache” could easily be considered one of the first top-10 rap records given Cheech and Chong’s Beastie Boys-like cadence, which predated hip-hop’s official commercial debut by more than five years.

But I digress. Back to “Basketball Jones,” clearly people were a lot less concerned about things like cultural appropriation—or, more accurately, Black mockery and racism—back then, which was ironic because the early ‘70s immediately followed one of the most “woke” periods in Black American history—the Civil Rights Movement.

Not long after “Basketball Jones” came more cultural fodder like CBS TV’s family sitcom “Good Times,” featuring eldest son J.J. (played by stand-up comedian Jimmy “J.J.” Walker) in full Black caricature mode. And remember this was also the era in which you were as likely to hear Louise Jefferson (Isabel Sanford) utter the N-word in a TV sitcom as you were Archie Bunker (Carroll O’Connor), maybe even more so. Some of those ‘70s shows have since come under fire by more enlightened people in the decades since they were hits, but they were clearly products of their era, not unlike “Basketball Jones.”

The point of all this? Well, not much really. There was plenty of bad parody to go around in the early 1970s; Cheech and Chong were just the best-known peddlers of it.

This is really just a reaction to the discovery that some of the best-known, most beloved musicians of then and now, played on “Basketball Jones” as if it were just another day at the studio. I’m just picturing George Harrison going from the sessions for Ringo Starr’s Ringo album, which he co-produced that autumn, to this; or Carole King running back to begin sessions for her Wrap Around Joy album after laying down those keys for “Jones.”

However it came to be, “Basketball Jones” is not something you often hear about when these artist’s names or their legacies are mentioned, and it certainly doesn’t change their tremendous accomplishments in music otherwise.

It’s just something you’re not likely to ever see happen again—superstars of their caliber coming together to record a song so horribly offensive to a particular group of people, all in the name of comedy, which, in this case, was a low point…even for Cheech and Chong.

DJRob

DJRob (he/him) is a freelance music blogger from somewhere on the East Coast who covers R&B, hip-hop, pop and rock genres – plus lots of music news and current stuff! You can follow him on Twitter at @djrobblog.

You can also register for free (below) to receive notifications of future articles.

Racist? Please.

I had no idea. George Harrison? Carole King? And others? I thought this was leading into a discussion of Ringo’s “Your Sixteen,” problematic but catchy as hell. (Isn’t that McCartney on kazoo?)

Lou Adler had some pull.

Yeah, Adler did. I’m a bigger “Photograph” fan than “You’re Sixteen,” but yeah that might have been problematic for a man who was in his 30s at that point. Lol

“You’re Sixteen” was actually a cover, which doesn’t make it any less cringeworthy. Then again, the same topic was also hit with a seventeen year old in “I Saw Her Standing There”.

Yeah, I guess the Beatles wanted to make sure they cleared any statutory rape thresholds with theirs. Ringo (sans Beatles), not so much!