(July 12, 2019). Warning: disco haters and Steve Dahl loyalists may not like where this is headed.

Recently, Chicago Tribune sportswriter Paul Sullivan – in an article commemorating the 40th anniversary of the infamous Disco Demolition Night at the White Sox’ former Comiskey Park on July 12, 1979 – had this to say: “the only time anyone mentions disco these days is when they’re talking about Disco Demolition, so it outlasted the genre. Congrats, Steve Dahl.”

Sullivan couldn’t have been further from the truth, except maybe in a circle of rock music purists who believe their genre of choice is as viable today as it was 30 and 40 years ago.

Probably closer to reality is that the only time the former Chicago-based shock jock Dahl’s name is mentioned these days is in conjunction with the Disco Demolition – a life-imitating-art example meant to mimic an ongoing Dahl radio show gimmick that should never have happened; an ugly stunt-gone-wrong that, in hindsight, was more moronic than it was culture-shifting.

To recap, Dahl regularly ran a gig on his morning radio show where he’d begin to play a disco record, only to have it end abruptly with a needle scratching and an explosion sound effect.

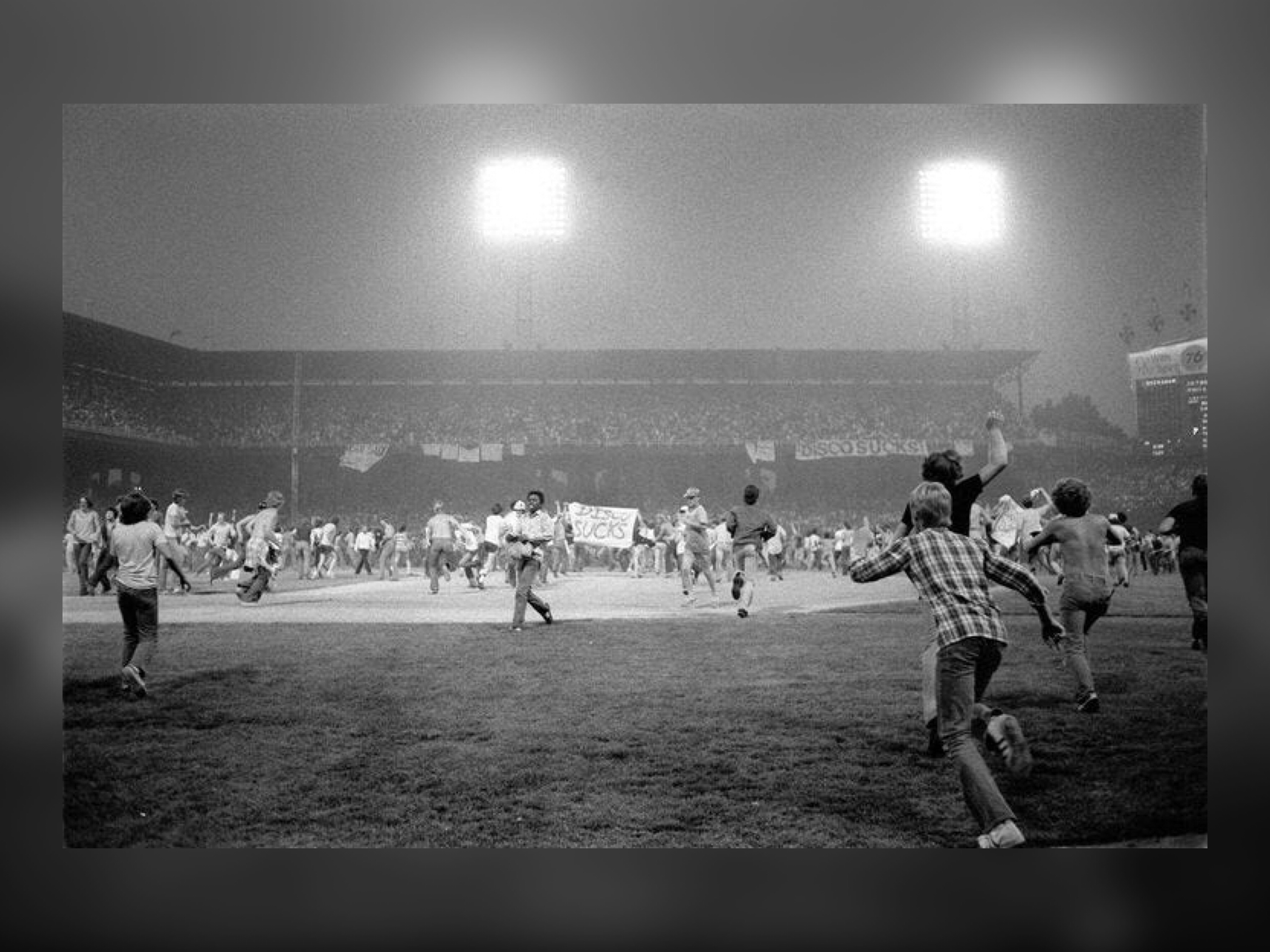

The goal of Disco Demolition Night at Comiskey Park on July 12, 1979, was for Dahl to recreate the radio gimmick with a real-life explosion of disco records on the field after the first game of a doubleheader between the White Sox and the visiting Detroit Tigers. The explosion did happen, followed by one of the ugliest music-related riots in history, in which thousands of mostly white youngsters and adults rushed the field to express their hatred of disco.

If anything, the hooliganism displayed at Comiskey Park that day in ‘79 has been more a subject for debate as to what motivated it (racism? homophobia? teenage angst? white male disenfranchisement?) than something that actually changed the course of popular music in America.

If the Disco Demolition deserves credit for anything, it’s for maybe hastening a death that was already happening, as label execs had already been questioning their involvement in disco given the low financial return on their considerable investments, which was affecting their bottom lines.

Throughout the first two-thirds of 1979, disco songs had dominated the pop music charts, with the genre occupying half or more of the top ten and a third to a half of the top 40 singles on Billboard’s Hot 100 in any given week between January and August 1979. In fact, on the first chart after the Disco Demolition in late July, the top six positions on the pop chart were occupied by disco records.

But the genre’s singles success didn’t translate to album sales. With few exceptions – Donna Summer, Chic and (reluctant disco act) The Bee Gees among them – most of disco’s success had been relegated to just singles sales with some of the biggest hitmakers failing to generate platinum albums.

In addition, each of the previous three years had seen blockbuster releases by Peter Frampton, Fleetwood Mac and The Bee Gees, all of which achieved massive sales. There were no such albums – disco, rock or otherwise – in the first half of 1979, and perhaps spooked by comparisons to the year before, when the disco soundtrack to Saturday Night Fever had broken worldwide sales records, the record industry decried 1979 – which saw a big drop off in revenue – as a bust year.

In hindsight, it was an unfair comparison as 1978 itself had been the industry’s high-water mark at that point. In fact, 1978 was so good (thanks mostly to Fever), that many labels spent the first half of 1979 increasing their commitments to disco. Labels like RCA, MCA and Motown established separate disco departments while WB and Atlantic expanded their existing ones, including hiring promotions directors devoted exclusively to disco.

Meanwhile, the radio side of the industry was at its own crossroads with the genre. Several prominent rock stations in major markets had converted from their longstanding rock formats to disco, causing many (white) rock DJs to lose their jobs, which no doubt fueled their anger towards the genre. (Dahl’s actions have been said to represent a solidarity stand he took for his brethren in rock radio.)

The dichotomy, however, was that disco’s radio numbers were still strong. Disco’s Arbitron ratings were regularly upstaging many of their counterparts, especially in the year’s first two quarters.

So here you had a genre that wasn’t selling well (at least as far as albums went) but was turning up great numbers in Arbitron (now Nielsen Music) ratings and on the singles charts. Plus disco, of course, was still popular in clubs – even the harder, rock-edged disco being touted by the likes of Summer, Blondie, Foxy and other popular acts.

Something had to give, and the powers that be at many record labels decided it had to be disco. After all, year-to-year revenue comparisons are what define success in many businesses, and the recording industry’s economics were no different.

As a result, when those hasty earlier investments showed sustained signs of not paying off like record execs had hoped, labels began to jump off disco’s bandwagon almost as quickly as they’d jumped on it, in many cases within mere months.

When labels stopped promoting disco records as hard as they had been previously, disco’s percentage share of the pop singles charts began to drop – slowly at first, before hitting rock bottom in the months and years to come.

When the somewhat opportunistic Steve Dahl organized Disco Demolition that July, the wheels had already begun falling off disco’s bandwagon. One could argue that had the disco sucks rally happened a year earlier in July 1978 – instead of July 1979 – it would likely not have been as associated with disco’s demise as it has been since. The dominance that disco enjoyed on the pop music scene from July 1978 to July 1979 would likely still have occurred, rendering the Demolition inconsequential.

And then there’s the question of disco’s death itself.

One could argue that disco as a music genre didn’t really die that day or at all in the immediate aftermath of the riot. For several months after Demolition, disco still had a decent share of the pop top ten and the top 40. For instance, over the next 18 months after Disco Demolition, through January 1981, eleven songs that reached the Billboard disco chart (including six between July 1979 and January ‘80) also topped the Hot 100, a crossover rate that was no worse than the years before Saturday Night Fever exploded.

That’s not to say that disco didn’t suffer a backlash; it clearly did, but largely due to its own excesses. By the end of August 1981, more than two years after Demolition, there were no disco songs in the pop top 40. Even more telling though, was the fact that there were very few songs in the top 40 by black acts in general, a sad reality that will forever connect the anti-disco movement to the issue of race and how black artists were impacted by disco’s downturn.

Which brings me back to the question of what motivated thousands of young, mostly white people to bum rush the field at Comiskey on that day in July 1979 and participate in the explosion of records by disco artists (and other non-disco black musicians) in the first place.

Steve Dahl has always contended that it wasn’t racism or homophobia (disco had a huge black and gay following) that sparked his radio gimmick-turned-riot at Comiskey. Instead, he states it was just a bunch of white guys and some gals who were expressing their frustration about being disenfranchised in the late 1970s (was that really even possible in America then?) as they saw their beloved rock music being marginalized by another brand of music – in this case disco.

Whatever the motivation, it’s certainly a myth to suggest that the Disco Demolition caused the death of disco. Or, at a minimum, that suggestion is an exercise in giving Dahl and his insider, White Sox organizer Mike Veeck (son of the team’s owner Bill Veeck) far more credit than history suggests they deserve.

In fact, disco never really died a complete death.

Yes, it lay dormant in the pop mainstream for a few years between 1980 and ‘82 while radio programmers tried to find their niche during a disco and black music backlash, but disco and dance came roaring back in the mid-to-late 1980s, albeit under various name changes like dance, house, freestyle, electronica, hi-NRG, EDM, etc.

In fact, of the 36 songs that occupied the No. 1 spot on the Hot 100 between January 1983 and December 1984, 26 of them made Billboard’s Dance/Disco charts (although several of those songs require some stretch of the imagination before they could be legitimately characterized as disco).

Still, dance music in all of its post-disco glory, with its various offshoots (including hip-hop) and it’s modified forms, continues to thrive today.

So was Steve Dahl’s Disco Demolition at Comiskey Park an historic – albeit ugly – occurrence? Maybe even a cultural touchstone event?

Indeed it was.

Its main premise (and perhaps the social undercurrent that sparked it) continues to galvanize disco and dance music haters annually – or at least decennially – with each passing anniversary. It will forever be commemorated in articles and – as the White Sox organization chose to do on this year’s 40th milestone occasion (albeit a month early) – with t-shirt giveaways.

But, to the larger community of music lovers, disco and dance music lives on in all of its modern day glory, despite perhaps Dahl’s or his followers’ beliefs to the contrary.

DJRob

DJRob is a freelance blogger who covers R&B, hip-hop, pop and rock genres – plus lots of music news and current stuff! You can follow him on Twitter @djrobblog.

You can also register for free to receive notifications of future articles by visiting the home page (scroll up!).

“More!, more!, more!, how do you like it? ?” . As a confirmed Motown baby, I’ve seen it all possibly. But disco’s beatdown didn’t kill it. It reconstituted itself into house music and other genres. Even artist such as Michael Jackson gave proof of its survival. “I will survive, hey hey?“ Disco reminds me of the movie The Wiz where Diana Ross, Micheal Jackson, Nipsey Russell and Ted Ross arrive in Emerald City and witness Quincy Jones deliver one of the hottest tracks. “How quickly fashion goes down the drain. Last week when you all was wearin’ pink Already for me red was old. The ultimate brick is gold. That’s the new color, children! Hit it!”

source: https://www.lyricsondemand.com/soundtracks/w/thewizlyrics/emeraldcitysequencelyrics.html

Lol. You’re a one-of-a-kind disco junkie!

Agreed — and I say that as one of those white kids who was weary of disco. (In New Orleans, where I grew up, an FM station became “Disco 97” and started beating the pants off the AM Top 40 monoliths — another sign of change.) I remember being thrilled when the Knack’s “Get the Knack” hit No. 1 — rock and roll, baby!

In retrospect, the rock was mediocre — it was the beginning of the rise of the tight-playlisted AOR monoliths. The best stuff was probably a hybrid — the New Wave of Blondie or the Talking Heads, which used elements of disco, or the changing focus of Donna Summer, whose “Hot Stuff” was a damned good rock record. But it’s hard to see that when you’re a 14-year-old white boy and feeling weird for actually liking that stuff.

Great comment, Todd! I was just 13 and not old enough to fully enjoy disco the way it was intended. But the music was right up my alley as it was the first genre I could say I grew up with. Ironically, I became more of a classic rock guy when I got older. Go figure!