(June 10, 2025). On June 9, I published a review of a track from Lil Wayne’s new album called “Bein’ Myself,” itself built around a lost 1973 Dionne Warwick gem called “(I’m) Just Being Myself.” It marked only the third time Warwick’s track had ever been sampled — and the first to lift her actual vocals from the tune.

Just hours later, the news of Sly Stone’s death began circulating across news feeds. And in that moment, my thoughts turned immediately to his own defiant anthem of selfhood: the slyly spelled “Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin),” a No. 1 hit that’s since been sampled more than 35 times — most notably in Janet Jackson’s militant “Rhythm Nation” and Brandy’s breezy ‘90s confection “Sittin’ Up In My Room.”

But Sly himself was the first to sample it. Or, rather, reimagine it.

On 1971’s There’s a Riot Goin’ On — Sly & the Family Stone’s fifth studio album and their first in nearly three years (after 1969’s Stand!) — he closed the LP with “Thank You for Talkin’ to Me, Africa,” a warped, slowed-down reinterpretation of that same No. 1 hit (all lyrics were the same as on “Be Mice Elf,” only the music changed). Gone was the full Family Stone band (although Sly credited them on the album), replaced by the multi-instrumentalist’s own raw, lo-fi funk backdrop. The track felt like a murmur from a troubled man drifting farther from the world — and possibly from himself. It was — as was the whole album it seemed — a rebuke of the astronomical fame he had achieved and the deferred dream of racial unity that was never realized as the turbulent sixties ended and seventies began.

Sly recorded most of There’s a Riot alone, at home, steeped in isolation and paranoia, addicted to drugs and weary from fame, estranged (at least temporarily) from his legendary bandmates — including sister Rose Stone, legendary bassist Larry Graham, vocalist Cynthia Robinson, and drummer Greg Errico — all of whom were either only partially present or absent altogether during its production.

And yet, from that darkness came his most artistically daring, sonically experimental, and politically charged statement: a record that critics believe still stands as one of the greatest albums of the rock era — and the only Sly & the Family Stone LP to ever top the Billboard 200.

A Silent Riot

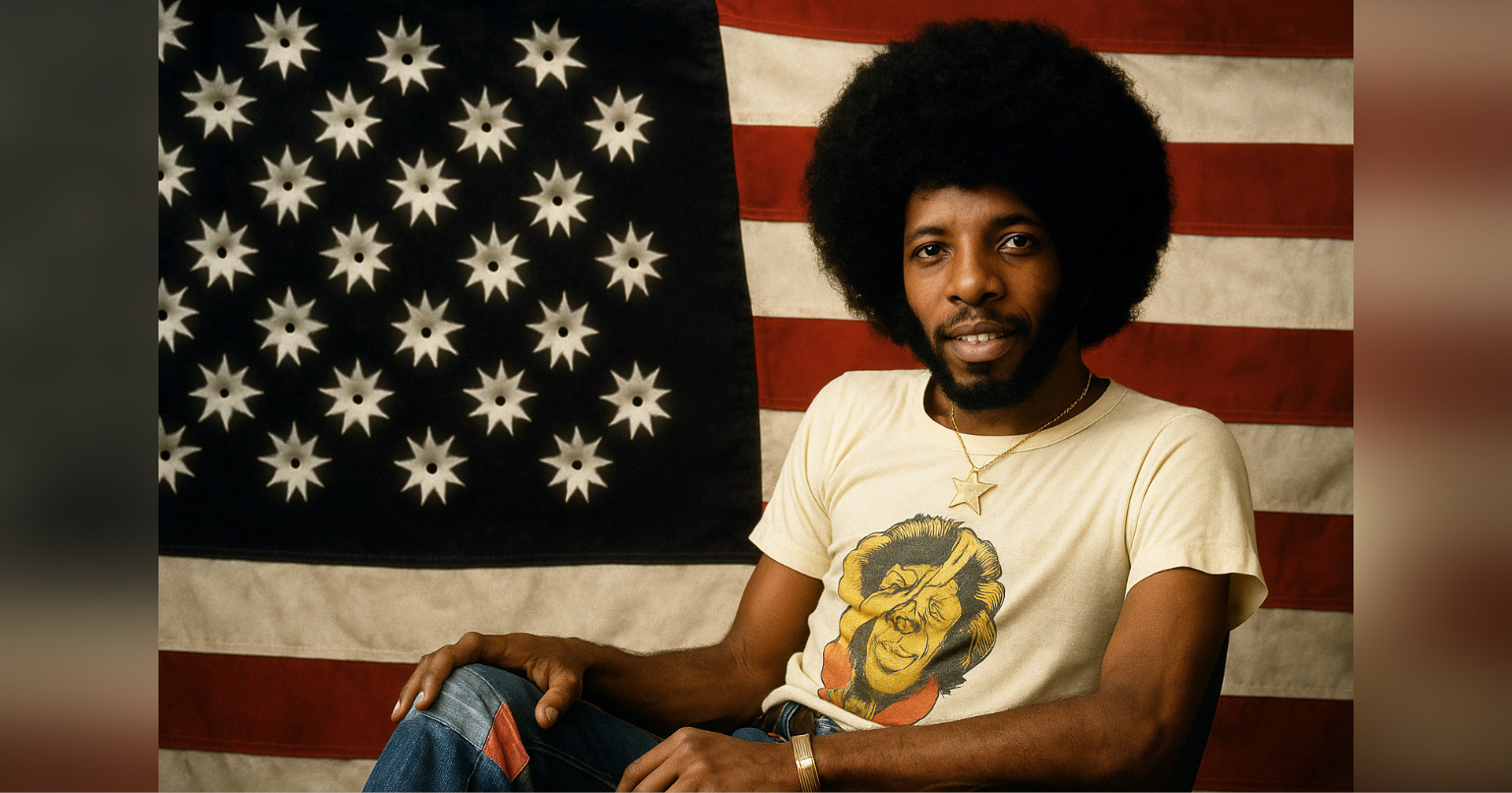

The title song “There’s a Riot Goin’ On” might be the shortest “track” in history at just under three seconds; it was famously presented without music or singing — just blank space, literally a prolonged transition from previous track “Africa Talks To Us” to the next one: “Brave and Strong.” Perhaps that silence was the statement. The title itself was a response, reportedly, to Marvin Gaye’s sublime social commentary What’s Going On, released just six months earlier. If Marvin was asking questions of a war- and riot-ravaged broken world, Sly was quietly conceding the answer was obvious, that it had already shattered him, and that there was nothing left to say. His America — post-‘60s civil rights struggle, deep in Nixon’s reign — wasn’t just troubled. It was unrecognizable, as the album’s cover depicting the U.S. flag with bullet holes replacing the stars would attest.

From the very first track, “Luv N’ Haight,” the album makes that disorientation clear. Built around a droning groove, staggered vocals, and psychedelic haze, it’s more jam session than structured song. The lyrics — when decipherable — hint at both spiritual longing and emotional resignation. And like much of the album, it’s not entirely clear who’s playing what. Was that Cynthia Robinson on vocals or still blowing the trumpet in parts? Maybe. Or maybe it was a tape loop. Sly’s grip on coherence — musical and mental — was clearly in retreat.

But even as the album spiraled inward to what could’ve been an implosion, it birthed two of Sly’s most enduring singles and my personal favorites from his entire catalog.

“Family Affair” and “Running Away” — Riot’s Shiniest Pop Moments

“Family Affair,” the biggest hit from the album, can be interpreted two ways: literally, as a reflection on familial dysfunction, or metaphorically, as a meditation on how society treats different groups of people. Sly famously croaks: “One child grows up to be somebody that just loves to learn / And another child grows up to be somebody you just love to burn.” Both are “good to Mom (America),” yet only one survives the system. The track was one of the earliest No. 1 hits to use a drum machine — a subtle detail that quietly revolutionized future funk, R&B, and hip-hop production, but one that underscored the absence of the Family Stone’s iconic drummer Greg Errico from much of the album’s sessions.

It’s been well documented that most of the album was recorded without the help of Sly’s former comrades. They had either walked away or been pushed out. How ironic then was it that the album’s biggest hit was “Family Affair,” on a project that clearly wasn’t one. By 1971, the “Family” in Family Stone had become more myth than reality (although Sly later said in interviews that he credited the group on this album because he didn’t want to be a fame hog).

Then there’s my personal favorite Sly Stone track of all: “Runnin’ Away.” On the surface, it’s playful — sunny even. But listen closer and it feels like Sly laughing nervously at himself. “Ha ha ha ha… you’re wearing out your shoes,” he teases about the notion of “Runnin’ away… to get away.” Get away from what though? Maybe it’s about a lover. Maybe it’s about his bandmates. Maybe it’s the spoils of fame. Or maybe it’s Sly mocking his own futile attempts to outrun the chaos that all of that created within him. I still think the line “The deeper in debt, the harder you bet” captures the sheer grip of addiction better than any one line in rock and roll history, and it couldn’t have come from a more credible source.

The Disintegration Behind the Genius

Beyond those singles — and the groovy but less successful third 45 “(You Caught Me) Smilin’” — There’s a Riot Goin’ On becomes murkier, both sonically and thematically. On “Spaced Cowboy,” for instance, Sly yodels loudly but croaks incoherently over a mechanized funk loop that feels held together by little more than his paranoia. The one line I could ever make out without looking at a lyric sheet was: “well, once I saw a boy who was a social whore…” That was either Sly thumbing up his nose at fame or indulged in self loathing, take your pick.

Running counter to that might have been “Brave and Strong,” a track that offered perhaps the album’s most hopeful melody with horn blasts and a slapping bass that recalled the group in its prime and was prototypical Ohio Players, even if the lyrics carried much of the same paranoia as the rest of the album (“Out and down, you ain’t got a friend… You don’t know who turned you in”).

And maybe that was the point. The album was both diary and hallucination — narcotized, fractured, and foreboding. If Stand! (1969) was Sly’s call to unity, Riot was his confession that he either no longer believed in that cause or that it would ever happen. Either way, the dream was no more.

Yesterday’s Riot, Today’s Headlines

And now, in one of history’s cruel coincidences, the man who gave us There’s a Riot Goin’ On has died as actual “riots” unfold again across America — most notably in Los Angeles, Chicago, Atlanta, and New York. The news of Sly’s death literally competed with protests against the current president’s immigration crackdown, racial profiling policies, and the deployment of federal ICE agents that have engulfed city blocks, just as Sly’s album once echoed the unrest of a generation from a half-century before.

It’s eerie how prophetic that album title feels today — 54 years later. A dream deferred indeed.

Legacy in the Shadows

Despite the hazy fog of its making — and perhaps because of it — There’s a Riot Goin’ On became Sly’s only No. 1 album. It’s frequently cited in lists of the greatest albums of all time, a blueprint for future funk, a precursor to lo-fi pop, one of the godfathers of hip-hop production and sampling.

But more than that, it’s the sound of a man unraveling in public, documenting his psychic collapse in real time — and (perhaps) accidentally creating a masterpiece. A riot, it turns out, doesn’t need volume to be violent. Sometimes it just needs truth.

As for the man himself, if There’s a Riot Goin’ On was his rock bottom, then it also marked the beginning of his journey to recovery, which he achieved to varying degrees of success over the next 54 years of life. If his was a death spiral waiting to happen, we should all be so blessed to get that kind of long-term prognosis.

Rest in power, Sylvester “Sly Stone” Stewart (March 15, 1943 – June 9, 2025). And thank you for talkin’ to us… and soundtracking the lives of generations of Americans, broken or otherwise.

DJRob

DJRob (he/him) is a freelance music blogger from the East Coast who covers R&B, hip-hop, disco, pop, rock and country genres – plus lots of music news and current stuff! You can follow him on Bluesky at @djrobblog.bsky.social, X (formerly Twitter) at @djrobblog, on Facebook or on Meta’s Threads.

You can also register for free (select the menu bars above) to receive notifications of future articles.

Well said! I think this album is so relevant at this period of time politically and socially. I’m reminded of the lyric from Stand! “Stand, you’ve been sitting much too long

There’s a permanent crease in your right and wrong. Stand, there’s a midget standing tall

And a giant beside him about to fall” RIP Sly.

I hope the “giant” in today’s world is about to take a huge fall.