(May 6, 2023). Theft or Influence?

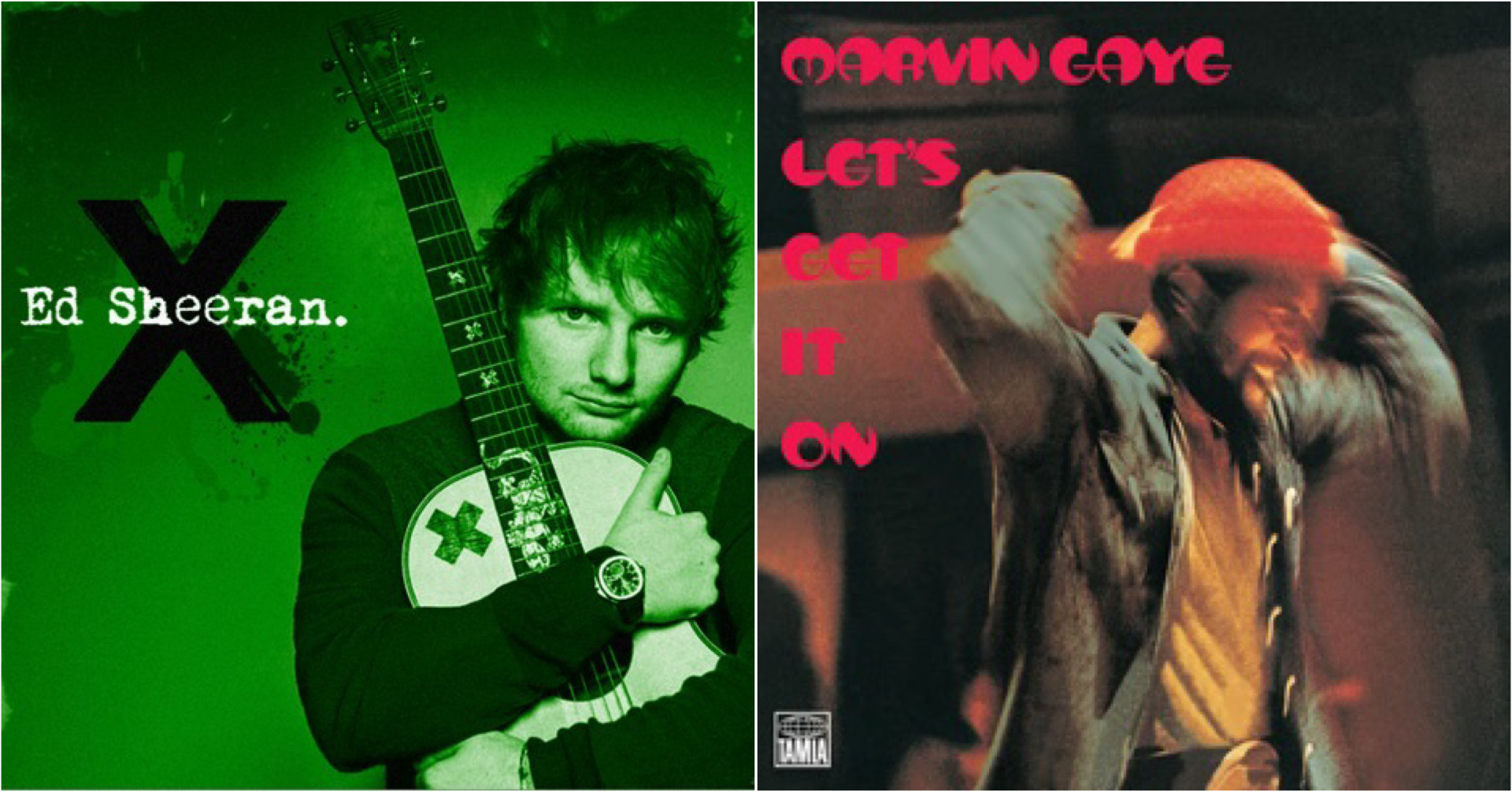

On Thursday, May 4, 2023, a Manhattan jury rendered its verdict in the highly publicized case of Ed Sheeran vs. Ed Townsend, a co-writer of Marvin Gaye’s 1973 No. 1 classic, “Let’s Get It On.”

Not guilty.

Or more accurately, not liable for his 2014 smash, “Thinking Out Loud” borrowing too liberally from the now 50-year-old soul classic co-penned by Townsend and Gaye, both of whom are now deceased.

Sheeran showed restraint but rejoiced while leaving the courtroom and speaking with reporters in a long speech that heralded the outcome as a win for future songwriters who draw inspiration from (but don’t intentionally copy) classics like Gaye’s, and referring to such claims as baseless and “criminal.”

But based on recent precedents involving other songs by both Gaye and Sheeran (more on those in a moment), this case was far from being a slam dunk win for Sheeran (and his co-writer Amy Wadge). It could have just as well gone the other way.

Yet the eventual outcome might have been foretold by a nearly 50-year-old Rolling Stone magazine review of “Let’s Get It On” by music critic Jon Landau.

Landau wrote in 1973: “the song centers around classically simple chord changes…” (emphasis added), suggesting even then that the chord sequence that Gaye and Townsend crafted for “Let’s Get It On” was not new (and certainly not unique or complex).

But it was that “simple” chord change—the four-chord sequence that makes up the bulk of “Let’s Get It On”—and its reemergence in Sheeran’s 2014 hit, that was at the center of the Townsend estate’s copyright infringement claim (Gaye’s estate was not a party to this lawsuit).

That chord sequence, plus the two songs’ percussive similarities (the “slow jam” beats are also not so unique, although reviewer Landau referred to the rhythmic arrangement in “Let’s Get It On” as “slightly eccentric” in that 1973 review), are what the Townsend estate and its legal team, led by civil rights attorney Ben Crump, claimed made “Let’s Get It On” a “cornerstone” in the American experience.

It was the “heart” and “soul” of the Marvin Gaye tune that Crump and company claimed was at stake in a trial that was about “giving credit where credit was due.”

One can imagine that Crump and the Townsend estate felt empowered by the results of recent litigation involving both Gaye and Sheeran, where contemporary artists had to pay up for making big hit songs in the 2010s that were too similar in nature to earlier classics.

In Gaye’s case was the infamous ruling against the makers of 2013’s “Blurred Lines,” which included singer Robin Thicke and his collaborators Pharrell Williams (who owned most of the writing percentage) and rapper T.I.

A jury determined in 2015 that Thicke and Williams had infringed on Gaye’s copyright for the 1977 No. 1 hit “Got to Give It Up,” and that they owed the Marvin Gaye estate more than $7 million in damages (later reduced by another court to just below $5 million).

Separately, in 2017, Sheeran conceded that he borrowed liberally (read: stole) from the 1999 smash “No Scrubs” by R&B trio TLC for his hit “Shape Of You,” and wound up modifying his song’s official publishing credits to include “No Scrubs” writers Kandi Burruss, Tameka Cottle (both of the ‘90s group Xscape) and producer Kevin Briggs—a move that guaranteed them publishing royalties on one of the biggest hits of the 2010s.

So if Sheeran was nervous about the years-long case involving “Thinking Out Loud,” he should’ve been. Precedent suggested that it could have easily gone the other way, particularly the “Got To Give It Up” vs. “Blurred Lines” ruling in which elements of both songs were dissected by musicologists similarly to how “Thinking” and “Let’s” were analyzed for their musical merits in the recently concluded case.

What’s more, in the earlier Gaye civil suit, the plaintiffs (the Gaye family) prevailed even though they had been prohibited by the judge from playing mashups of the two songs (intended to demonstrate just how closely constructed they were) to the jury.

What chance did Sheeran have in a case where mashups of the two songs in question were allowed?

Not surprisingly, Crump and crew pounced on the opportunity and reportedly played in their testimony a mashup of “Let’s Get It On” and “Thinking Out Loud” to prove their similarities (the songs are similar, and Sheeran wasn’t disputing that…but listen for yourselves in the two audio clips below).

But Sheeran’s testimony used what amounted to reverse psychology to show that not only did he not copy “Let’s Get It On,” but he would have been an idiot to do that and then perform mashups of the two songs in concerts (which he did during his subsequent tours). Again, Sheeran acknowledged the two songs’ similarities.

The British singer then followed—reportedly—by using a similar mashup to dissect the two songs and show how he constructed “Thinking Out Loud” independently with Amy Wadge, without copying “Let’s Get It On.”

The jury ultimately agreed, noting that the elements of “Let’s Get It On” that were central to this case were not copyright protectable, meaning that “simple” chord sequence—and the song’s soulful, but “eccentric” percussive beat—were basic song building blocks that could not be owned by any songwriter, in 1973 or now.

I can’t help but think that, in addition to the technical merits of the case, two other factors likely diminished the Townsend estate’s chances of victory.

One was that they were not joined by Gaye’s descendants in these proceedings. The late Motown superstar’s lawyers, which didn’t include Ben Crump, had prevailed years earlier in the “Got To Give It Up” vs. “Blurred Lines” win, despite some differences in the two songs’ construction—like certain musical note patterns, melody, etc. They were able to prove, however, that there were enough similarities—background vocal arrangements, bass note patterns, keyboard parts, and that unusual percussive arrangement among them—to allow “Got To Give It Up” to prevail.

And second was the Crump factor.

Crump is a civil rights attorney (not an entertainment lawyer) and his mere presence in this case gave (at least this observer) the impression that this trial was as much about social issues as it was the technicalities involving song construction, with terms like “heart” and “soul” being used to support his claim (although I’m sure the musicologists doubling as forensic experts were using more technical terms in trial).

But neither of those non-technical factors mattered in the end.

What did matter was that the Manhattan jury established yet another precedent, one that said the “classically simple chord change” used in “Let’s Get It On” was just that: classic and simple, and available for songwriters everywhere who dare to be inspired by Marvin Gaye in the future.

DJRob

DJRob (he/him/his), who is not an entertainment lawyer, is a freelance music blogger from somewhere on the East Coast who covers R&B, hip-hop, pop and rock genres – plus lots of music news and current stuff! You can follow him on Twitter at @djrobblog.

You can also register for free (below) to receive notifications of future articles.