(May 3, 2023). In an era where “story songs” were as common in popular music as novelty records, one particular song stood high above the others: Gordon Lightfoot’s “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald,” a haunting, six-and-a-half minute accounting of what it must have been like for the final crew aboard the huge iron-ore shipping vessel whose fatal voyage across Lake Superior happened on November 10, 1975.

Lightfoot, a folk music hero who considered “Wreck” to be his greatest work, died Monday, May 1, 2023, in his native Toronto, Ontario. He was 84.

It was nearly 47 years earlier, in the autumn of 1976, when the late singing/songwriting legend memorialized the 29 crew members and The Edmund Fitzgerald in a tune that this blogger considers to be the greatest story song of all time, a song whose haunting melody and gripping narrative inspired by a real-life tragedy has brought more than a few tears upon repeated listens.

But what made it the greatest?

The story-song sub-genre contains many memorable examples, especially from the 1970s era in which “The Wreck of The Edmund Fitzgerald” was a smash hit.

And even the sub-genre had sub-genres. If you wanted campy fiction, you could find it in all three of Cher’s No. 1 singles between 1971-74 (“Gypsies, Tramps & Thieves,” “Half Breed,” and “Dark Lady”), or in Vicki Lawrence’s 1973 smash “The Night The Lights Went Out In Georgia.”

“Dark Lady” and “The Night The Lights Went Out” could be easily grouped with Helen Reddy’s “Angie Baby” in the domestic murder mystery (or not-so-mystery) sub-heading.

If you preferred period-appropriate preachings about the virtues and pitfalls of interracial mixing, you could do no wrong with The Stories’ tale of increasingly common, but still taboo, black-and white love in the No. 1 1973 hit “Brother Louie” or the earlier “Society’s Child” by pop singer/songwriter Janis Ian.

If fictionalized military heroes (or non-heroes) were your thing, you could find them in popular ditties like “Bad Bad Leroy Brown” (a fictional accounting of a man based on a real person Jim Croce knew from the US Army) or “Billy, Don’t Be a Hero” by Bo Donaldson and the Heywoods.

That latter tune had also been recorded by the British group Paper Lace, whose fictional accounting of police-gangster conflict in the Windy City played out in another seventies No. 1 hit, “The Night Chicago Died.”

But those songs—all huge hits—paled in comparison to Lightfoot’s “Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald,” if for no other reasons than the compelling, poetic way in which the iconic Canadian musician told the story and the music bed he created that was befitting of his poignant lyrics.

Beginning with the song’s basic musical structure, it was composed as a variation of the “sea shanty,” a kind of maritime work song that traditionally was sung to accompany rhythmic labor aboard large shipping vessels (like the Edmund Fitzgerald).

In this vein, the song was constructed without any chorus or bridge, just an ominous melody that repeats with little variation from that first steel guitar pluck that opens the ballad all the way to the song’s final fade. (Was it a coincidence that a steel guitar was used so prominently given the boat’s load of iron ore and connection to the steel industry?)

And while the melody of “Wreck” was catchy—or, more appropriately, seared into listeners’ memories—the song hardly builds towards a climax musically.

The only escalation is when the first drum notes kick in at the 1:34 mark and a few synths are added for dramatic effect. Otherwise, the instrumentation sort of meanders along, much like a large shipping vessel like the Edmund Fitzgerald might have sailed on calmer seas.

Similarly, Lightfoot’s vocals maintain their same tone and cadence in all seven verses, with no change in inflection, no key modulation or octave change, and certainly no vocal acrobatics or ad libs. Perhaps the only color he intentionally adds is the three-syllable way in which he pronounces “Detroit” in the song’s final (seventh) verse.

All of that must have been intended to have the listener focus on the story, not the song or the artist, with Lightfoot showing a level of reserve and reverence that some of the other great vocalists and storytellers of his time rarely displayed.

The enormity of the tragedy—the ship’s ultimate fate not mentioned until three minutes into the song—was juxtaposed perfectly against Lightfoot’s bland, matter-of-fact delivery. Yet he still compels as he gives a gripping visual of the circumstances and events that preceded the calamity.

He casually describes the ship’s cargo (iron ore pellets) and the massive weight of it (26,000 tons), which were the result of business terms secured by steel companies beforehand.

He also mentions conversations that he imagines must have happened in the hours leading to the ship’s demise. Even if they weren’t on the mark, you can visualize the doomed men aboard that ship having said just those things, or something very similar.

Gordon’s use of metaphor (“that good ship and true was a ‘bone to be chewed’”) and regional nicknames (Lake Superior was known by Chippewa tribes as ‘Gitche Gumee’; the late autumn storm was characterized as “the witch of November”) simultaneously gave vividness and legitimacy to the song.

What also made “Wreck” so compelling was the sensitivity Lightfoot displayed in devoting as much time to the wreck’s aftermath as he did the events leading to it, beginning just past the song’s halfway point when he expresses the common human reaction to the tragedy by questioning where the love of God goes.

With sensitivity and compassion to the Great Lakes shipping community, Lightfoot described the history and geography of the area, with each of the five Great Lakes getting a name-check and the rest of the country gaining an appreciation of what the upper Midwest already knew about Gitche Gumee and the “gales of November.”

Like a reporter, except with the kind of compassion and sympathy that news reporters often lack, Lightfoot speculates on what might have caused the shipwreck, noting the shift in wind direction (from north to west blowing), the rough seas, and a main hatchway that caved in.

Days after the actual wreck, the 729-foot-long, 75-foot-wide, and 39-foot-tall ship was found broken into two large pieces on the sea floor just 17 miles north of Whitefish Bay, the safe harbor of which would have likely saved the sailors’ lives had they been able to reach it on that fateful day of its final voyage.

Those facts lend credibility to Lightfoot’s song’s speculations, although he’d only written it a month or so after the tragedy occurred (he had been inspired by a Newsweek article covering it).

Although every great story song has a beginning, middle and end—and the Edmund Fitzgerald’s wreck alone would have been an understandable way to end such a tragic story—Gordon didn’t allow the ship’s sinking to be the last word.

Instead, he provided closure by giving the 29 men—for whom the ship’s wreckage serves as a final resting place—the memorial they and their families deserved.

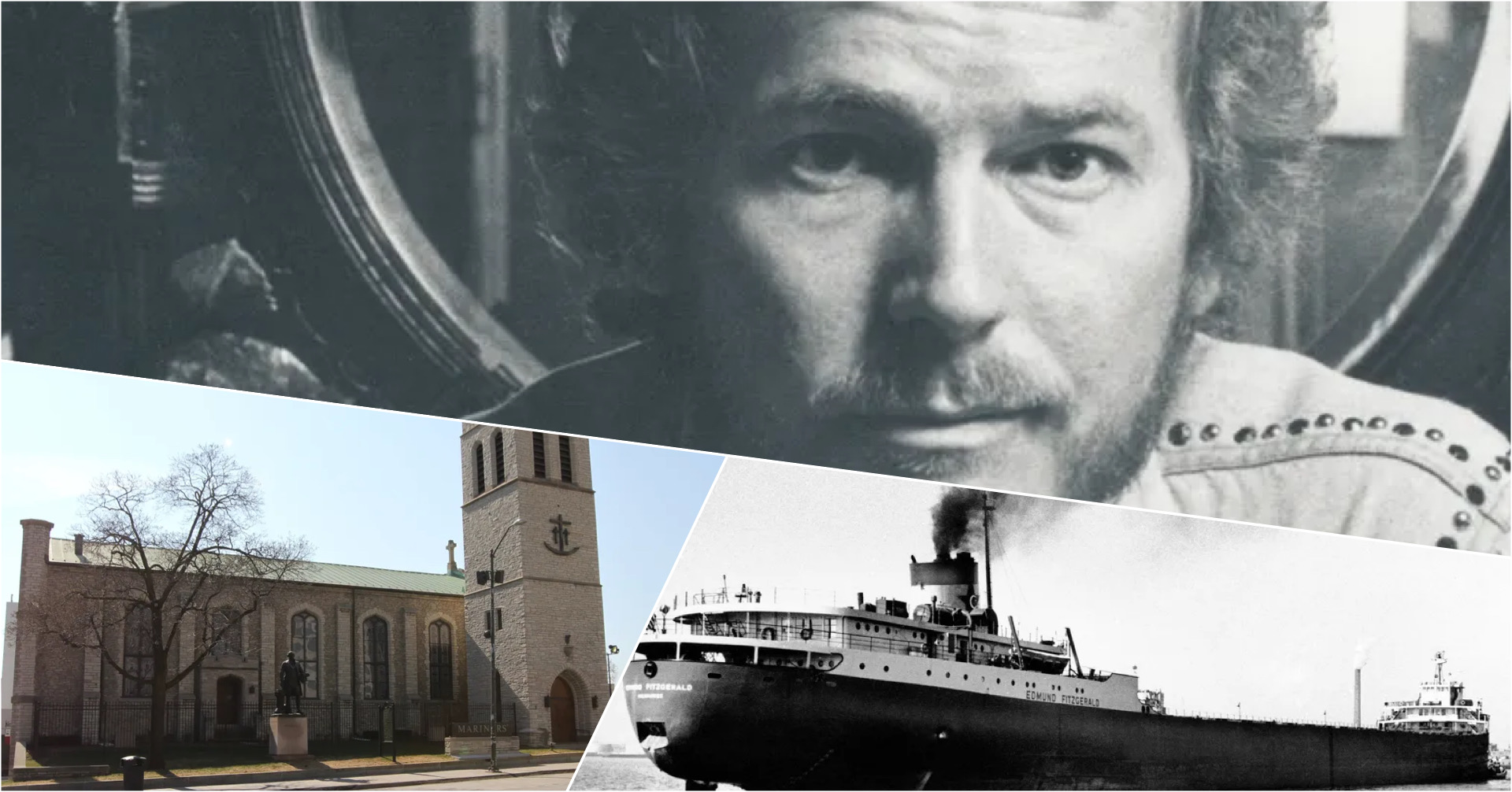

“The church bell chimed ‘til it rang 29 times for each man on the Edmund Fitzgerald,” Lightfoot croons in the ballad’s last verse.

That bell-ringing tradition has since happened annually in observance of the shipwreck and in honor of those 29 men, with an additional chime for all the lives lost in the roughly 6,000 shipwrecks on record in all five Great Lakes: Superior, Michigan, Huron, Erie and Ontario.

But what caps the greatness of “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald” was its timing, which added to the song’s sentimental value.

Released in September 1976, just as the first anniversary of the actual tragedy was approaching, the song’s peak impact occurred in November, reaching No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100 just days after the anniversary, on the chart covering Nov. 14-20, 1976.

Even more poignantly, “Wreck” reached No. 1 in Cashbox—Billboard’s rival at the time—during the tragedy’s anniversary week (on the chart dated Nov. 13).

It also reached No. 1 in Lightfoot’s native Canada and is still highly regarded today—as is its artist—by members of the Great Lakes community on both the American and Canadian sides of Lake Superior.

And while Lightfoot’s accounting was well embraced by those impacted by the wreck, he has made concessions to the families and locals as more facts became known over the years.

After being informed that the “musty old hall in Detroit” where the men were memorialized was not, in fact, musty, he would change that lyric to “rustic old hall” in live performances.

He would also—out of respect for the families—remove any references to the “hatchway caving in” during live performances as it was speculated and later concluded by federal investigators that the crew hadn’t battened down all the hatches before the ship set sail on Nov. 9, a possible contributor to how it took water and sank.

Also importantly, it was found through interviews with the captain of another ship (the Arthur M. Anderson) that had closely trailed the Edmund Fitzgerald that day, that the doomed ship’s captain’s last radio message at 7:10 pm wasn’t that “we had water coming in.” Instead it was “we are holding our own.”

Ten minutes later, the ship had disappeared from view and from the second ship’s radar…doomed to its eternal resting place on the sea floor.

But Lightfoot remained true to his art, electing not to remove the original lyrics from “Wreck Of The Edmund Fitzgerald,” and noting in later interviews that he would not make changes to copyrighted material.

In summary, there were many elements that made Lightfoot’s story song one of the most compassionate, most sensitive and most compelling story songs ever.

Perhaps no element contributed more to that assessment than the very real events that the song described, in a manner that respected the lives lost and the families they left behind.

And now “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald” is part of the legacy that Gordon Lightfoot leaves behind.

Rest in eternal peace to one of the greatest songwriters of an era.

Gordon Lightfoot (1938-2023).

DJRob

DJRob (he/him/his), who will update this article with pics taken at Whitefish Point and the Mariner’s Church in Detroit, is a freelance music blogger from somewhere on the East Coast who covers R&B, hip-hop, pop and rock genres – plus lots of music news and current stuff! You can follow him on Twitter at @djrobblog.

You can also register for free (below) to receive notifications of future articles.