By January 1972, Queen of Soul Aretha Franklin had firmly established herself as the First Lady of Music, with no other being her equal. In just five short years with Atlantic Records, she had racked up nineteen singles that reached number three or better on the R&B chart, including eleven No. 1s, with all of those crossing over to the top 30 of the pop chart as well…and that was just between 1967-72.

Having covered pop and soul tunes written by some of the most legendary songwriters in history, including Lennon & McCartney, Burt Bacharach & Hal David, Ashford & Simpson, Paul Simon, Otis Redding, Elton John & Bernie Taupin, and others, Aretha had already shown there was no song, songwriter or genre she couldn’t conquer.

That fact – and an apparent desire to return to her irrepressible church roots – are what likely fueled the soul queen’s decision to record the famous Amazing Grace double album – one that stands as the best-selling live gospel album of all time and the best-selling LP of Aretha’s long career…even with it not producing any of the dozens of top-40 hits the late legend accumulated over the years.

Amazing Grace sold more than two million copies in 1972 – a lot for an album by an R&B artist in the early ‘70s – which was as much a testimony to Aretha’s undeniable talent as it was to the album’s spiritual authenticity. No other R&B singer at the time could have pulled off such a live recording so convincingly and few, if any, dared even try.

Thankfully, the event was also captured on film, with Warner Brothers executives (Atlantic was a fully-owned subsidiary of WB by then) intending to capitalize on Aretha’s immense popularity by having the documentary slated for theatrical release later that year.

While Amazing Grace the album was released that June, the “concert film” – directed by the late Sidney Pollack – never saw the light of day, initially due to technical issues that prevented the video and the audio from being synced properly, and later because of decades of legal wrangling between Aretha and the film’s would-be producers and distributors.

That is until recently – just months after Aretha’s passing in August 2018. With the Queen’s reservations either being properly addressed prior to her death or by virtue of her no longer being around to prevent it, Amazing Grace finally premiered in theaters last fall.

On a recent Sunday, I got to see the film at Chicago’s Landmark Century Centre Cinema, and it did not disappoint.

In a word, the movie, or rather, the experience was incredible!

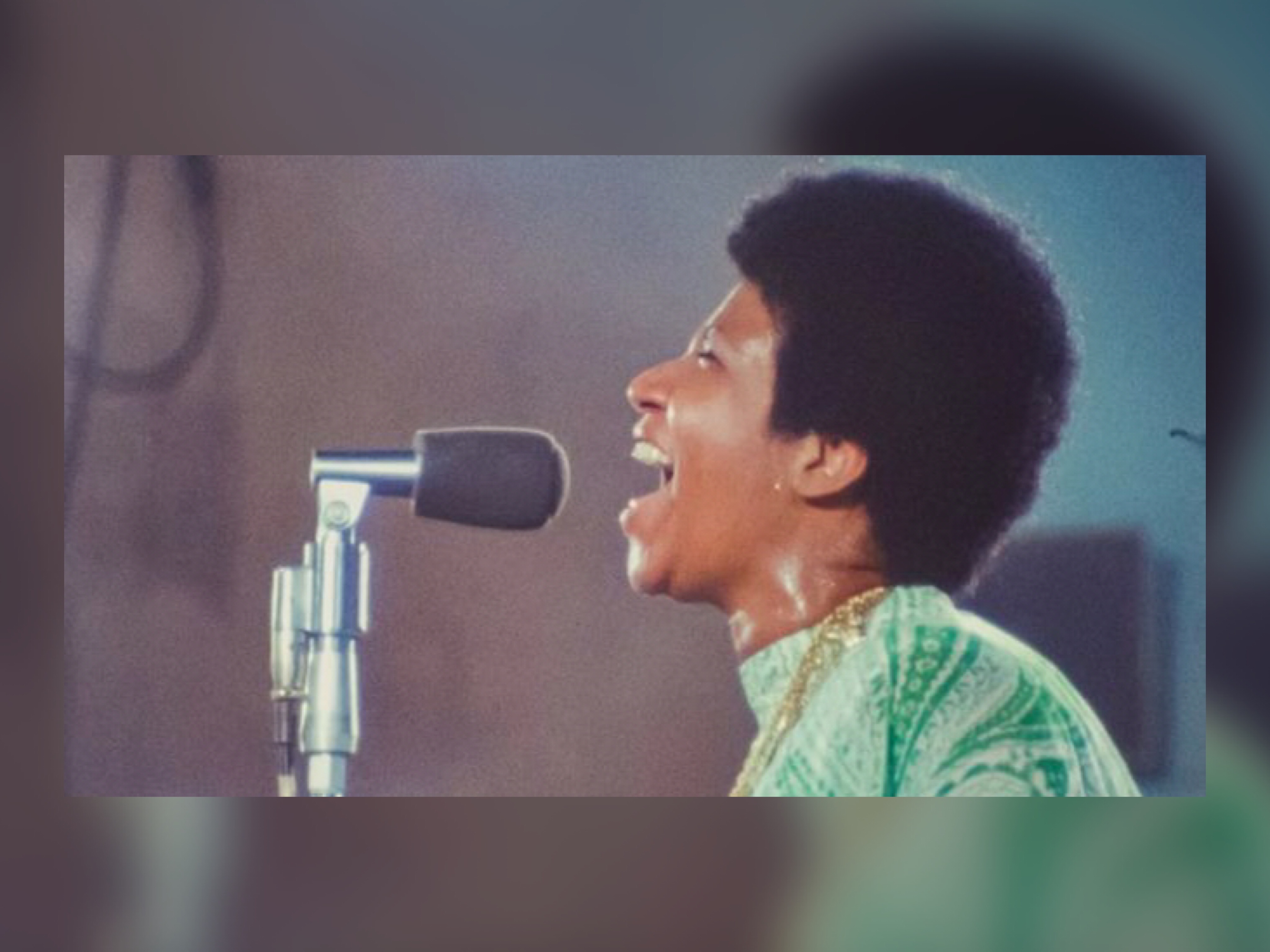

Recorded over a two-day period in January ‘72 at the New Temple Missionary Baptist Church in Los Angeles, and curated by the late Reverend Dr. James Cleveland, Amazing Grace was Aretha at her spiritual best. It was a return to her gospel roots on an album that she’d poured her sweat and tears into – literally.

Both the movie and its 47-year-old soundtrack captured Aretha filled with the Holy Spirit and surrounded by fellow believers whose energy she no doubt fed off as she sang the gospel. It would take more than one hand to count the number of times “sing, Aretha!” was heard coming from the mouths of parishioners in awe of her performance.

Yet the movie revealed some key moments about the album’s creation that no audio recording alone could do proper justice.

First there was the church itself – the black church – which was as much a part of this event as the Queen herself was. As Reverend Cleveland is heard saying in the film’s first few minutes, Aretha could have easily decided to record this album in the studio, but she wanted the “full church experience” instead.

And it was the full experience that she – and, by extension, we viewers – got.

While you certainly don’t have to regularly attend a black church to appreciate the musical messages in Amazing Grace, you’d almost had to have stepped foot in one to understand its cultural significance in the black community and why Aretha chose this setting to record the album.

Take the choir for instance.

In this case, it was Reverend Cleveland’s Southern California Community Choir, which as he put it, had to be on “a thousand” for this performance. Under the direction of a very impressive (and very expressive) young director, Alexander Hamilton, the choir’s primary job was to sit there and sing the gospel behind the biggest guest vocalist they’d likely ever accompany.

For his part, Hamilton enthusiastically gestured with his hands, controlling the choir’s every section – the tenors, the sopranos, the bass – as any good director would. Yet interspersed throughout were the full-body jerks and head movements that had him on the verge of breaking out some pretty funky dance moves. He appeared to show restraint but, given the circumstances, who among us wouldn’t also have been so inspired?

As for the choir itself, they held their own, too. Not only did they pull off a solid vocal performance, but the moment didn’t appear to overwhelm them. For the most part the two dozen or so of them remained calmly seated – behind Aretha – punctuating her vocals with their own as they elevated their voices to the four or five microphones strategically positioned in front of and above them. The unorthodoxy of their seated positions dawned on me about three songs in, as church choirs normally stand up while they sing the Lord’s praises.

I chalked up their position to the producers’ desire to get the best audio recording of their voices possible given the few microphones on hand. Either that, or they simply wanted to have the same seated perspective of the Queen as everyone else in attendance did on the two days of recording.

Eventually though, Aretha’s singing, or perhaps the Holy Spirit – or both – moved many of the choir and churchgoers to stand and rejoice as the diva belted out one familiar tune after another. In one instance during Day 2, with Aretha singing the traditional hymn “Never Grow Old,” a woman clad in red and clearly consumed by the Holy Ghost stood at her pew, became emotional and began flailing about… stomping and wailing uncontrollably before falling to her knees. Those seated nearby gave her assistance and she eventually regained her cool, but not before earning the prize for most outward display of emotion on either day.

Churchgoers have all seen that woman before – at our own churches. It’s something you have to witness to understand, and the film captured the visual moment in a way the album obviously couldn’t.

The music itself was equally compelling, with the film giving more context behind each song’s recording as well as their original sequencing, which was different from that of the album.

Aretha opened Day 1 with Marvin Gaye’s “Wholy Holy,” a song he’d released the year before on his mostly secular What’s Going On masterpiece.

The Queen followed that with the more traditional hymn “What A Friend We Have In Jesus,” a tune that prompted the Rev. Cleveland to note that, as a Baptist minister’s daughter, Aretha likely had to learn some of these hymns before she could do anything else as a little girl.

It was the grown Aretha, however, and the album’s namesake tune, that created the most unexpected emotional moment. “Amazing Grace,” the nearly 200-year-old hymn, or more accurately Franklin’s stirring 10-minute rendition of it, moved Rev. Cleveland so much that, midway through the song, he abandoned his seat at the piano and moved several rows behind it to bury his face in his hands to hide his tears. This was after he revealed only minutes earlier during the song’s introduction that Aretha herself had been moved to tears while rehearsing “Amazing Grace” the day before.

Then there was the heat. Despite the dates on the calendar, it must have been hot in church those two January days. There were several times during recording when Aretha’s brow had to be wiped of perspiration. At one point in the film, Rev. Cleveland is heard summoning someone to get her a glass of water (bottled water didn’t exist then).

Viewers got to appreciate other nuances as well, like when Aretha and the musical director discussed which key the next song would be played in before delving into the jubilant “How I Got Over,” a tune written by Clara Ward – the gospel legend who made an appearance during Day 2.

Clara Ward and the Reverend James Cleveland were two of Aretha’s biggest influences, along with Mahalia Jackson (as her father later noted), but no one likely inspired her musical career more than her dad himself, the Reverend C. L. Franklin, whose own appearance on Day 2 was another treat.

The two ministers Cleveland and Franklin both doted over Aretha during the film, and she appeared reverent and humbled by the attention. When her father emerged, you could almost see in Aretha the desire to make the rest of her performance perfect for the man she had accompanied on so many church tours as a child growing up in Detroit.

This was most evident during her performance of “Climbing Higher Mountains,” a song introduced by Rev. Cleveland as being “borrowed from” Aretha’s father. After singing the opening line, perfectionist Aretha – detecting a flaw that the untrained ear couldn’t – directed the band to stop and start again from the top as the elder Franklin sat in the audience observing his daughter.

There were other big names there as well, including Aretha’s Atlantic label mates Mick Jagger and Charlie Watts of The Rolling Stones. Seeing a young Mick Jagger in a mostly black church clapping wildly to gospel tunes was a sight indeed. And for added historical perspective, this was the same Mick Jagger who only months earlier had a No. 1 song with the Stones’ most controversial tune “Brown Sugar,” a song about, well, I’ll let readers think about that for a second.

A spectacle perhaps, but just seeing what went into the recording of such a classic album as Amazing Grace was a music lover’s delight. Seeing it being done by Aretha and those in her inner circle at the time was divine. That it occurred in the black Baptist Church – with all its hallowed traditions on full display – was something no audio recording alone could ever do total justice.

Aretha was at the peak of her vocal powers and in full command of her voice during the two days of recording. There were no tricks, no apparent overdubs, no special studio effects, no theatrics. Just the Queen humbly and proudly baring her musical soul for her Lord and Savior with the kind of conviction one could not possibly fake.

In a career full of signature, game-changing moments, it would be easy in retrospect to lump this performance with the many iconic ones Franklin would give over her nearly 60 years in show business, like singing at MLK’s funeral in ‘68, or being a last-minute stand-in for Luciano Pavarotti during the ‘98 Grammys, or singing during the first black president Barack Obama’s inauguration in 2009.

They were all historic, career-shifting moments indeed.

But Aretha singing for the church and to the Lord was where it all began for her, and nothing she’d done before or since would capture her true roots like Amazing Grace.

We may never really know if it was Aretha’s wish to have the film released posthumously in this way, but I think the Queen of Soul would have been proud of the final product.

DJRob

DJRob is a freelance blogger who covers R&B, hip-hop, pop and rock genres – plus lots of music news and current stuff! You can follow him on Twitter @djrobblog.

You can also register for free to receive notifications of future articles by visiting the home page (scroll up!).

Great read!!