(April 24, 2023). At a time when we were pushing—with Stevie Wonder among those leading the charge—to have Martin Luther King, Jr.’s birthday recognized as a national holiday, and when Michael Jackson’s label was “negotiating” to get his videos played on mostly white MTV, there was another prominent social issue that Black folks in the music industry were dealing with, one that came to a head exactly 40 years ago and which involved a certain brewing company that is once again at the center of musicians’ protests.

Only back then, the protests were largely about the lack of inclusion and opportunities for a group of people—namely Black Americans—while today’s protests, done by right-wingers who were somehow offended by Anheuser-Busch’s inclusion of a transgender female in one of their marketing campaigns, are, ironically, because the beer company was guilty of being just that: inclusive.

It’s a clear case of history unrepeating itself: prominent Black people fighting in 1983 (both with AB and within our own ranks…more on that in a moment) to gain equity within the halls of the largest beer manufacturer in North America, versus prominent non-Black people today engaged in a culture war with the goal of exclusion.

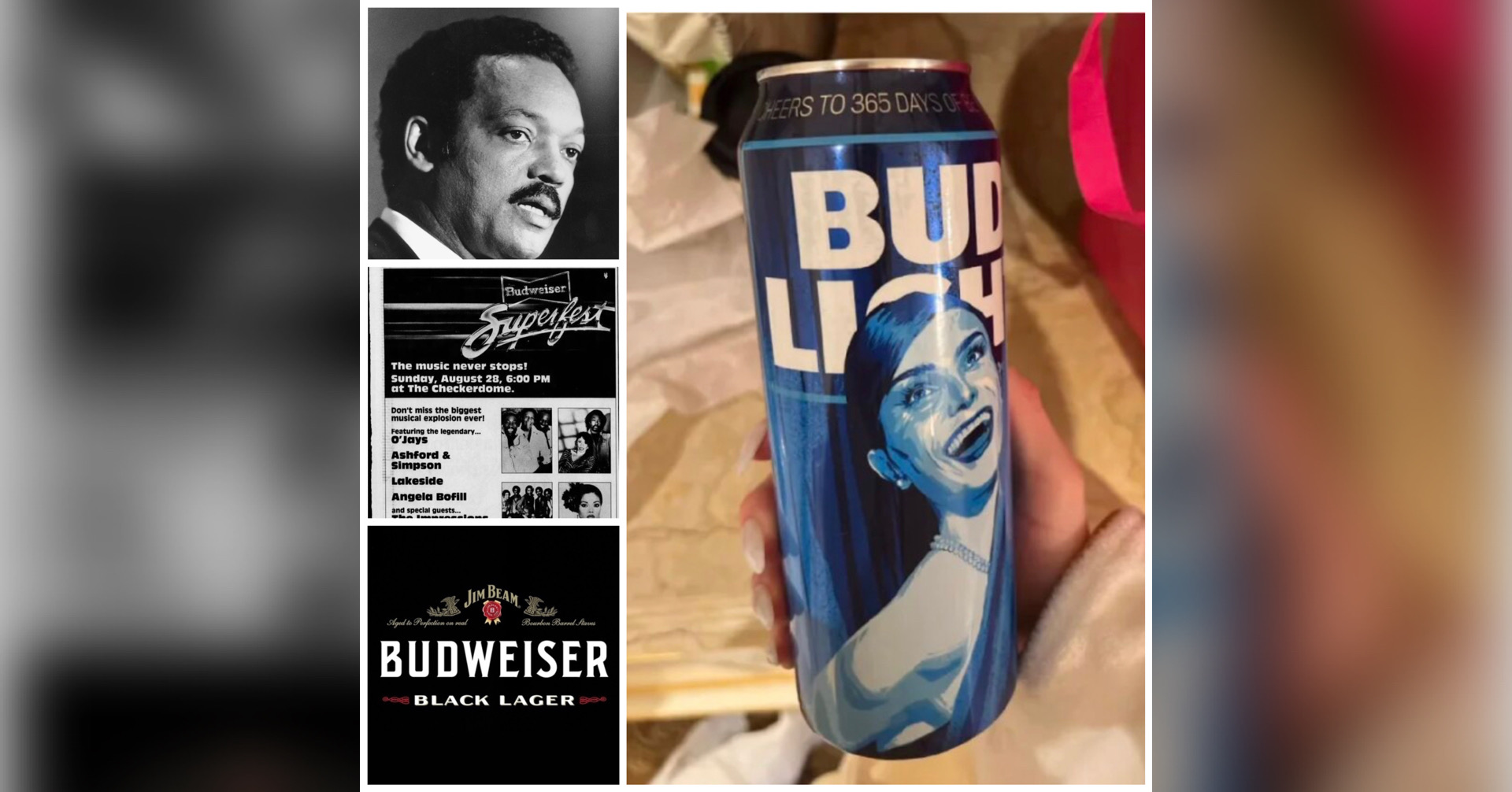

Actually, the current battle is one that Bud Light—a product of AB—boldly entered into last month when it featured social media influencer Dylan Mulvaney in a “March Madness” campaign to commemorate her one-year transition from male to female, but then sheepishly retreated from weeks later when the going got too tough.

That tough-going came in the form of several musicians-turned-social influencers—namely well-known conservatives Kid Rock, Travis Tritt and Ted Nugent—expressing their outrage over Bud Light’s decision to feature (and thereby include) Mulvaney.

Kid Rock—in the kind of performative protest that he and other right-wingers once shunned the left for—went so far as to set up target practice with Bud Light cans and then post a video of himself gunning them down with an AR-15. Country singer Tritt announced the removal of all AB products from his concerts’ hospitality rider. And “Cat Scratch Fever” guy Nugent called the Budweiser decision “the epitome of cultural deprivation,” although it wasn’t made clear exactly who was being deprived of anything.

The issue of transgender acceptance and inclusion (and their basic human rights/dignity/safety) has been a polarizing one for years, especially in recent times as businesses and governments make slow progress towards providing accommodations for gender-nonbinary people in bathrooms, competitive sports and other institutions.

The issues reportedly at the center of the 1983 protests—spearheaded by the Reverend Jesse Jackson’s Operation PUSH organization–were also polarizing, but a little simpler to digest back then.

Organizers like PUSH, which stands for People United to Serve Humanity, and the NAACP wanted to increase the number of Black distributorships (of Anheuser-Busch products), to increase Black employment at the executive levels of AB, and for AB to do more advertising in Black-owned media (like Jet and Ebony, and BET at the time).

Perhaps the only similarity between the Black protests of Anheuser-Busch in 1983 and those of anti-Trans malcontents in 2023 is that they both involved musicians.

The Rev. Jesse Jackson had begun the protests in 1982 (and carried them into ‘83) because of the issues with representation of Black people within AB’s corporate structure. But he was keenly aware that AB also operated a series of popular Black-oriented concerts every year known as Budweiser SuperFest. The beer company was slated to run the 1983 tour from July to September that year.

Among the artists slated to perform was the legendary George Clinton, who, according to an article in Cashbox magazine (June 11, 1983) was tapped to headline the first stop of the tour on July 8 in Long Beach, California. (Clinton happened to have the No. 1 song on the soul chart exactly 40 years ago today with “Atomic Dog.”)

Other artists scheduled to perform throughout the tour included big R&B/funk names of the day like Kool & the Gang, the O’Jays, Con Funk Shun, Sly Stone, Peabo Bryson, Angela Bofill, the Bar-Kays, Lakeslide, Rick James and the Mary Jane Girls.

And therein lie the dilemma within the Black community. Here was Anheuser-Busch—the largest beer-maker in the country promoting a highly popular concert series geared towards our people—at the center of a protest from key Black institutions because of its lack of Black representation.

To further the cause and complicate matters, Jesse Jackson, then 41, successfully recruited the National Association of Black Promoters (NABP), a coalition of the nation’s top independent Black concert promoters and production companies, to support PUSH in its protest.

And the main target of NABP’s boycott was the upcoming SuperFest concert series.

Except some individual promoters apparently had dissented from the NABP protest and felt that the issues with Black representation within the brewing company’s ranks had little to do with the SuperFest situation, where show promoters felt the upcoming concerts were creating jobs within Black communities that otherwise wouldn’t exist.

Furthermore, individual Black promoters were cut in on a 50/50 deal with SuperFest’s national promoter—a white guy by the name of Michael Rosenberg—to promote the shows in specific local markets. The 50/50-split was an improvement on the 60/40 deal (favoring Rosenberg) from the previous year’s festivals, and from an earlier time in SuperFest’s then-four-year history when Black promoters had been ignored altogether.

In essence, Black concert promoters were just now getting their feet in the door of marketing a big-time concert series, and some felt they couldn’t allow the protests to rob them of an opportunity to both create jobs for Blacks and show that they were capable of handling this type of event with the goal of “running them ourselves eventually.”

Also complicating things was the fact that some artists, like the Solar Records group Lakeside (whose big hit at the time was “Raid”), had reportedly entered into a “legally binding” verbal commitment to perform at that first show on July 8, 1983, despite Solar (pronounced SO-lar) label president Dick Griffey having expressed support for the Operation PUSH-led boycott of the tour.

Griffey, who had earlier in 1983 issued some very strong statements in favor of boycotting AB’s SuperFest, saw the issues with the tour’s dealings with Black promoters and the diversity problems within the brewing company as intertwined.

He felt that a 50/50 partnership with Rosenberg’s company (Marco Productions) was simply not enough and that Black promoters should have it all when it involved promoting concerts in our communities involving our artists. He used the analogy that we didn’t see Black promoters being given half of the money for Rolling Stones or The Who concerts (he had a point), so why should it be that way in reverse?

He, like Jackson, felt that the diversity issues within Anheuser-Busch’s executive ranks and that company’s willingness to hire Marco Productions to handle the SuperFest nationally, needed to be addressed together.

So where did this all end?

Well, the concerts went off without a hitch. Tickets were priced at $15 a pop (in 1983 dollars) with shows grossing over $110K in the earliest venues that July. While not sellouts, attendance for those shows numbered in the 7,000 to 8,000 range, not bad considering the economic times (and the controversy involving SuperFest and AB).

Regarding the Operation PUSH boycott of Anheuser-Busch, the Rev. Jesse Jackson announced that September that his organization was endorsing a program of “enhanced opportunities for Black America” put forward by the brewing company, thereby ending the year-long protest.

According to an archived article from The NY Times (September 10, 1983), the new deal included “taking a variety of hiring and promotional steps, increasing the use of Black-owned businesses, making deposits in minority-owned banks, and advertising in minority-owned publications.”

That deal was expected to put $320 million dollars in Black communities over the ensuing five years (my inflation calculator puts that at nearly $1B in 2023 dollars).

Both Jesse Jackson and August Busch, III, then-president and chairman of the beer company, whose meetings largely orchestrated the deal, sounded conciliatory notes in the end, with Busch acknowledging his company’s “proud” but not “perfect” record in their interactions with Black people and other minorities, and Jackson noting that, through better communication, he became aware of the St. Louis-based company’s previous generous contributions to local minority causes.

On that note, there weren’t many other companies in 1983 as large as AB willing to use a Black R&B singer like Lou (“when you say ‘Bud’”) Rawls as a corporate symbol and sponsor a national campaign to support the United Negro College Fund, which Budweiser had done for years.

Back to the present day, the Black protests of Anheuser-Busch in 1983 are largely forgotten (they’re not even mentioned in the company’s Wikipedia entry under the “Controversies” tab).

But today’s controversy regarding transgender inclusion is now front-and-center for the company who, after launching the original March Madness ad, retreated into silence for weeks (and sidelined its marketing VP Alissa Heinerscheid who oversaw the campaign) before Brendan Whitworth, AB’s current CEO, issued a lengthy patriotic buzz-word filled, non-trans-committal statement about its history of supporting its “communities, military, first responders, sports fans and hard-working Americans everywhere.”

Whitworth added: “we never intended to be part of a discussion that divides people. We are in the business of bringing people together over a beer.”

Can’t you just see it now? Kid Rock and Ted Nugent chopping it up with Dylan Mulvaney over a Bud Light with beer cans bearing Mulvaney’s image?

Nah, I can’t either. That ice-cold brew would have a better chance of surviving hell.

A better look for AB would have been to stand by its initial support of Mulvaney and transgender people nationwide, even doubling down on its original campaign. The side-stepping they did to avoid further angering people like Kid Rock, Tritt and Nugent only left the beer company stuck in some murky middle ground with both sides wondering where it really stands.

But like most protests and boycotts, this current one too shall pass (remember, we Black folks didn’t like the NFL a few years ago…and come to think of it, neither did a lot of white folks, albeit for different reasons).

In a year’s time, all will be okay in Anheuser-Busch’s world, and these protests and boycotts will blow over. Many of the offended won’t even realize they’re drinking AB products like Stella and Michelob.

And the company will realize that its decision to feature Mulvaney was at least a small step in the right direction, as its “deal” with Black folks was forty years ago.

DJRob

DJRob (he/him/his), a Miller Lite guy who drinks Bud on occasion, is a freelance music blogger from somewhere on the East Coast who covers R&B, hip-hop, pop and rock genres – plus lots of music news and current stuff! You can follow him on Twitter at @djrobblog.

You can also register for free (below) to receive notifications of future articles.