(Aug. 6, 2020). In 1977, before there was Breakfast in America, Supertramp’s megahit album from 1979, the British prog-rock/pop outfit released the nugget that was Even in the Quietest Moments, an album of seven songs spanning 44 minutes, one tenth of which belonged to the opening track and iconic signature tune, “Give A Little Bit.”

As a longtime Supertramp fan, one who’s binged many times on the group’s catalogue and who is moving ever deeper into his 50s, I have come to appreciate the quieter moments in my own life, as well as Supertramp’s Quietest Moments…so much so that my two old music-loving cohorts and I thought it would be neat to have this month’s “Three Old Guys” feature be about the album that would be the appetizer setting the band up for its biggest meal ticket two years later.

Not the greatest initial reception.

The album Even In the Quietest Moments was met with mixed reviews upon its initial release. For example, Graham Hicks – a writer for the Brandon Sun out of Brandon, Manitoba, Canada – wrote in the paper’s April 30, 1977 edition that Supertramp “has badly bombed with Even in the Quietest Moments,” calling it “a plodding album, without the dynamics, vitality and urgency of Crime of the Century.” Crime was the group’s first North American release in late 1974 and one Hicks incidentally considered the “best album of 1975.”

Conversely, a reviewer for the Richmond Review (Richmond, British Columbia, CN) in April 1977 called Moments Supertramp’s best album yet of their three North American releases up to that point, which included Crime and 1975’s Crisis? What Crisis?. Citing the band’s individual elements, including saxophonist John Helliwell, whom he likened to Junior Walker “turned on to” John Coltrane, writer Bob Beech wrote “(Moments) is their best record to date and will probably be their most memorable.”

As for that last part, to borrow another of the group’s album titles, those were indeed “famous last words.”

As it turned out, the six million copies sold of the band’s next album – Breakfast In America – would render Beech only half right about Moments, and even that half was arguable, considering the amount of praise heaped on Crime of the Century two years earlier (as well as Hicks’ not-so-flattering review of Moments noted above).

But even if its success was sparked by only one big hit single – the ear worm that was “Give a Little Bit” – the gold-certified Moments was certainly a step in the right commercial direction for a band who had plodded its way through four prior albums (there were two non-North American releases prior to Crime), and which had generated only mixed consumer response during their seven or eight years of existence prior to 1977.

So now what do we think?

Now, with 43 years of added historical perspective and steady dieting on Supertramp’s most popular tunes – including those before and after our feature album – DJROBBLOG’s Three Old Guys revisit Even in the Quietest Moments and its seven tracks, from those first familiar strums of Roger Hodgson’s twelve-string acoustic guitar on “Give a Little Bit,” to the odd orchestral finish that concludes his “Fool’s Overture” – and everything else in between.

But, before we get to each old man’s unique take on the album, here are some quick facts about Supertramp and Even in the Quietest Moments you need to know:

Album Release Date: April 10, 1977

Producer: Supertramp

Songwriters: Roger Hodgson and Rick Davies (credited jointly like the Beatles’ Lennon and McCartney, each man wrote their songs separately and sang lead on their own compositions). Hodgson wrote tracks 1, 3, 5 and 7; Davies wrote 2, 4 and 6.

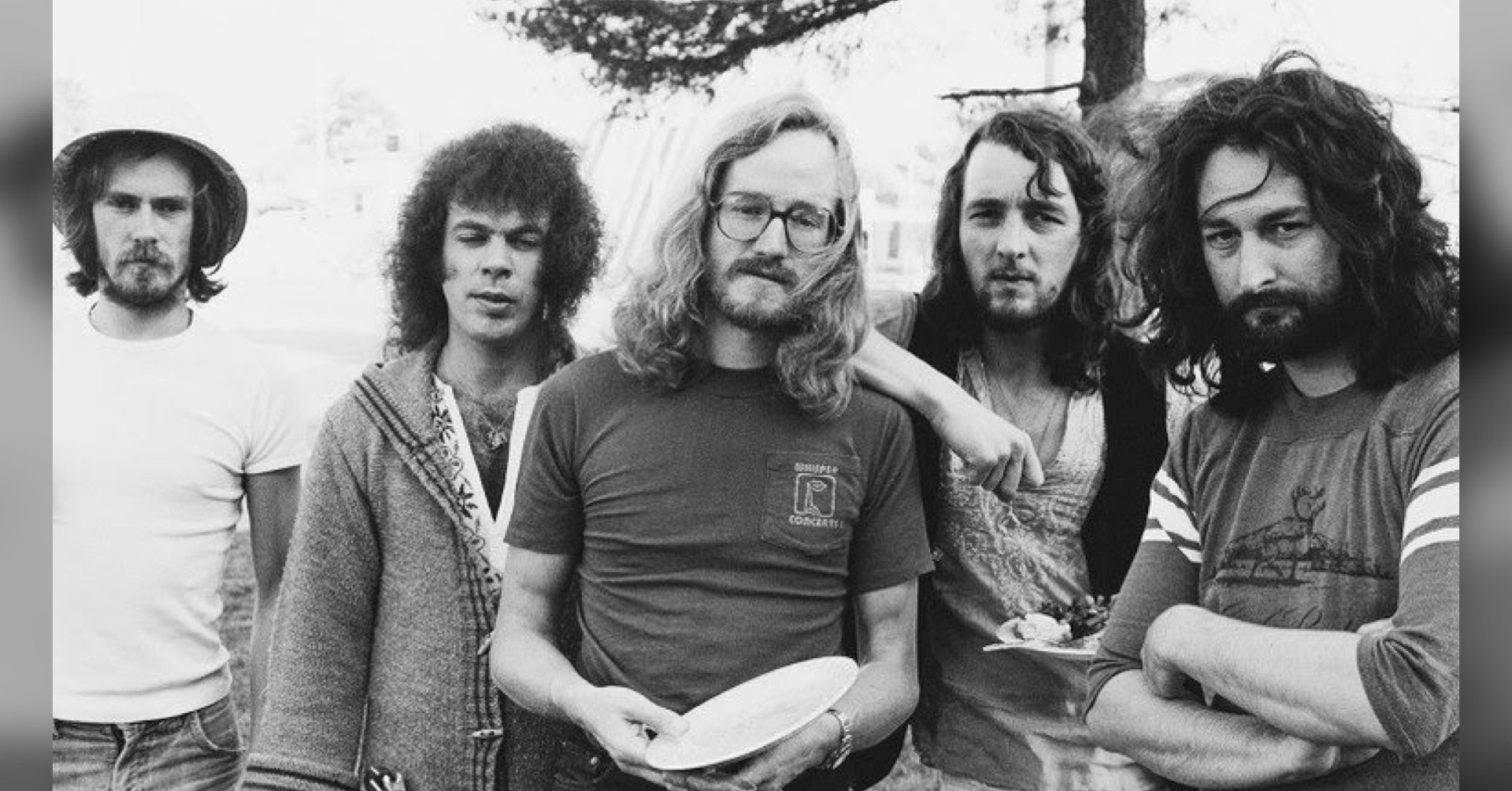

Supertramp were: Rick Davies (vocals, keyboards); Roger Hodgson (vocals, keyboards, guitar); John Helliwell (sax, backing vocals); Dougie Thomson (bass); Bob Siebenberg (credited as Bob C. Benberg; drums, percussion).

And, for even more context, these were the top-three best-selling albums in America during the week before Quietest Moments’ release, according to Billboard (chart date April 9, 1977):

- Hotel California – Eagles

- Rumours – Fleetwood Mac

- Songs in the Key of Life – Stevie Wonder

In other words, it’s easy to see how Quietest Moments could be so easily overlooked in a year that included blockbusters like those three (and many others).

So now here are those three old curmudgeons who would like nothing more than to go back in time and relive their youths, but today find themselves living out their fantasies of being music critics of the albums that defined their childhoods. Here are the three separate takes on Even in the Quietest Moments by DJRob, Bloomberg and Dean Michaels.

DJRob:

Unlike Canadian writer Bob Beech quoted above, I wouldn’t have gone as far as to ever compare any of Supertramp’s music to anything Coltrane did, but I’ve always thought Helliwell’s sax to be the band’s most underrated element, and one of its most essential – behind the signature keyboard and piano playing from cofounders, principle members and songwriters Roger Hodgson, whom I had the honor of seeing in concert nearly four years ago here in Chicagoland, and Rick Davies, the other half of their talented creative team.

On Even in the Quietest Moments, all those elements and more came together in what was the first album the band recorded entirely in the United States after spending most of their studio time on the other side of the pond (perhaps this experience was the inspiration for the next album’s title, Breakfast In America?).

Admittedly, I didn’t discover Moments until decades after its release, and that was only after I made a conscious effort to explore Supertramp’s deep back catalog after having owned Breakfast and a couple of their greatest hits compilations on compact disc. In fact, aside from Roger Hodgson’s “Give A Little Bit” – ostensibly the only track pop radio would’ve touched back then, even if they had released a followup single stateside – I had discovered songs like Hodgson’s “Babaji” and Davies’ “From Now On” long before I’d heard this album from which they originally came, thanks to the various anthologies.

In fact, over the years, “From Now On” has emerged as one of my favorite Supertramp tunes. The way Davies’ introduces his ballad with that saloon-style piano intro before other instruments are added and he wistfully sings about being stuck in a rut, then contemplating a life of crime before boiling it all down to the realization that he’s just “living in a fantasy”? To me that was rock poetry.

That he allowed this conclusion to play out in a rousing finish with a gospel-like vocal arrangement in a call-and-response refrain, while Helliwell compellingly wraps his sax around the tune‘s coda, makes “From Now On” the most soulful song on the album, bar none.

But I’ve jumped way ahead, so let’s get back to the album’s song sequence, shall we?

It wasn’t until more recently that I discovered deeper cuts like Davies’ “Lover Boy,” the album’s second track. Unlike “From Now On,” this track’s piano intro is deceptively Motown-esque (between Hodgson and Davies, Davies clearly has the most soul in Supertramp).

And “Lover Boy” also uses a call-and-response arrangement, except, unlike the climatic finish of “From Now On,” Davies invokes partner Hodgson for a bit of back-and-forth during the song’s second verse. I’ve always enjoyed Davies’ Hodgson-like falsetto vocals when they’re smoothed out to complement his otherwise gruffness. It’s just too bad there isn’t more of this switch-up between his two personas on this album.

“Lover Boy” has all the stylings of Supertramp’s earlier prog-rock material, with a long arrangement that uses changing tempos and various segments that on first listen seem disjointed, like a hodgepodge of two or three songs mixed together. But one can detect a cohesiveness and structure to the song after repeated listens. It just doesn’t come close in quality to Davies’ earlier, better works like 1974’s “Bloody Well Right” and “Rudy” from the album Crime of the Century… or even “From Now On” from this album.

After “Lover Boy,” Hodgson returns for the title track, and a reminder of why this album really is his for the taking. The title ballad is arguably the second-best song on Moments, after his own “Give a Little Bit.” “Even in the Quietest Moments” builds from a subtle intro, where it sneaks up on you with a prolonged synthesizer note and a prominent 12-string acoustic guitar (played by Hodgson) with a clarinet accompaniment – again, courtesy of Helliwell – before Hodgson begins the lullaby-like vocal proceedings.

“Even in the Quietest Moments” is another of the band’s six-minute opuses, this one building from that subdued beginning to a compelling climax as Hodgson’s spirituality (a place he frequented) beckons for the sun not to fade away while Davies repeats a background chant with an unintelligible lyric that seems to reflect the same sentiment but actually contradicts it (my resourceful fellow reviewer Bloomberg clears this up in his piece below). All of this builds to Hodgson holding a long 14-second note similar to the 10-second one he bellows at the end of “Give a Little Bit” just two tracks earlier. It’s this crescendo that yields to a reprisal of the song’s earlier bars during the final verse where Hodgson’s 12-string takes center stage again.

Next up is “Downstream,” which is essentially a Davies solo track – it’s just him and his piano for the entire song. At exactly four minutes, it’s the shortest cut on the album. And, despite a Billboard magazine review in April 1977 touting it as the album’s best cut, this song is the one I’ve played the least.

Not that “Downstream” is a bad song, it’s not. It just seems more by-the-numbers than anything else on Moments, with Davies’ very Burt Bacharach-ish piano riff carrying the ballad from start to finish. Or worse, except for some chord changes here and there, I could easily overlap that piano riff with the one used in Debby Boone’s “You Light Up My Life” from later that year, and you’d be hard-pressed to deny the schmaltzy similarities.

After “Downstream,” the musical rollercoaster ride that is Hodgson-Davies-Hodgson-Davies continues with “Babaji.” And, except for sixth track “From Now On,” the album’s up-and-down-and-up again quality seems to follow this pattern as well, with Hodgson riding most of the ups. (Davies would have much better moments on Breakfast two years later.)

“Babaji” is Hodgson’s ode to Mahavatar Babaji, an Indian yogi and deity. Fittingly, it’s probably the most strident of the seven tunes on Moments, even if it battles with “Fools Overture” as the album’s most self-indulgent with Hodgson’s typical excesses playing out throughout the track. Regardless, A&M Records gave it a single release in Europe and Australia, while bypassing it here in the states. That was probably a smart decision on the label’s part, as I can’t see many U.S. top-40 station program directors giving this one a lot of spins – even back then.

After Hodgson’s rousing ad-libs close “Babaji,” Davies brings “From Now On,” which I’ve already gushed over, followed by Hodgson’s very progressive, Alan Parsons-like closing track, “Fool’s Overture.”

Most of “Overture” is instrumental, with a long, five minute-plus intro that takes up exactly half of the song’s 10:52 and incorporates excerpts from a famous WWII wartime speech by British PM Winston Churchill, before we finally hear Hodgson’s high voice abstractly singing about history and, well, Churchill – or so it seems.

“Overture” has over the years been a Supertramp fan favorite – one the band often played at its concerts and one Hodgson still includes among his faves. He fashioned it as three separate pieces of music that he’d written over the years – pieces that finally came together for Moments.

Indeed, it’s the song’s title that graces the sheet music appearing atop that snow-covered piano on the album cover, even if it’s not actually the song’s sheet music.

In that sense, “Fools Overture” was slighted twice – first on the album cover’s fake sheet music image and then in a decision where that song was also supposed to be the album’s title, except for a late change that allowed Even in the Quietest Moments to prevail.

Hodgson likely didn’t mind, since they both were his songs – as was the most successful song from the album: the band’s signature tune, “Give A Little Bit.”

Regarding that classic, there’s not much that hasn’t already been said about one of the biggest musical pick-me-ups to ever grace radio. “Give A Little Bit” is the song with that perfect pop melody and a shuffling drum beat undercurrent that first introduced me to Supertramp in 1977 (I didn’t discover their earlier stuff until long afterwards).

As such, “Give” will always hold a special place in my heart (even if Billboard didn’t bother to include it among the album’s “best cuts” in its April 16, 1977 album review). The fact that the song’s universal message of unselfishness has touched so many generations all these years later just seems to validate our earliest fandom of the classic tune.

Without “Give A Little Bit,” we certainly wouldn’t be discussing Moments now.

But I’ll let Bloomberg and Dean Michaels explain it better…

Bloomberg:

1977, and the outrages and crudities and musical minimalism of the punk revolution are capturing the attention of the music media world. And at the same time, certain pop performers are flaunting their indifference by, instead, fashioning their works to be ever more elaborate/ornate and studio-rific, whether it’s the overegged hooks-upon-hooks-upon harmonies of ELO, the Springsteen-derived teen-opera parodies and Cinemascopic saxophony of Steinman/Meat Loaf, the theatricality of disco visionaries like Moroder/Costandinos, or the lush envelopment of Supertramp’s slow-burning arrangements.

For a short few years in the 1970s, Supertramp scored big with their own particular sound that was halfway between prog and pop, between Elton and Floyd, with maybe a bit of the Steely Dan-eyed character portraiture typical of the period.

Again and again (with one exception), these songs accumulate drama through additive dynamics and a beautiful recording job rather than energy; and if the approach sometimes suggests the Beatles in their painterly “Pepper”/”Abbey Road” mode, partially attribute that to mixing engineer, Geoff Emerick himself.

Alternating lead vocals and songwriting are Supertramp’s own John & Paul, co-head songwriters Roger Hodgson (mewling earnestly through four self-penned songs) and Richard Davies (more bluesy & relaxed on his three), and they contribute so many indelible melodies, that the absence of rock ‘n roll energy (Hodgson’s occasional semi-raunchy feedback notwithstanding) and abundance of mid-to-leaden tempos can be overlooked.

Also absent, strangely, is Davies’ familiar buzzy Wurlitzer e-piano, replaced by regular piano and augmented in places by up-to-the-minute polysynth-sequenced urgency. Arrangements are adult, tasteful, with John Anthony Helliwell’s woodwind commentary the dominant solo voice as they build, and build, and retreat and build again. It’s quite a bit longwinded; some of these codas do extend themselves needlessly, with fake endings and endless fades, possibly a byproduct of only having writing seven originals.

Anyways, let’s have a listen.

Side One, track one, and Roger Hodgson’s introductory “Ooooh….yeah!” and splashy 12-string strums introduce the very famous “Give A Little Bit” (“of your love to me/…my life for you,” etc.), the obvious hit single here. (#15 USA, #8 Canada.) A rare Supertramp song built around acoustic guitars, it’s such a breezy collection of exhilarating hooks that the nothing-special lyric takes on anthemic qualities, and Hodgson’s very high, slightly sobby vocal approach is full of joy here.

There’s a climactic fake ending, the first of several throughout this album; a key change in the final minute transforms the coda into a celebratory dance around the maypole, and it all winds down with a delicate arpeggio.

Richard Davies’ “Lover Boy” follows, beginning with lighthearted music-hall piano shuffle to accompany its blase depiction of a pickup artist. The beat plods; the music turns from charming to something much darker, as the orchestrations and slow-burning David Gilmourish axe take over, and Davies’ leisure-suited subject’s sordidness oozes everywhere: I love that the guy lives near a shoe store and singles bar, and that his swinger’s manual has a “funny” title. The music keeps getting thicker, clots, fades away on a piano stutter…only to return for a encore that’s slightly pointless, but does provide Roger a bit of additional solo time.

Similarly stretched out, but in a nice stoned modal-earcandy way, we have the title cut. A pastiche of “Dear Prudence” and other White Album pastoralisms, it finds Hodgson fingerpicking amongst beckoning Helliwell clarinet obbligatos, and fretting about misinterpreting those moments of silence when he can’t hear either his lover or his Lord, I’m not sure which. Or something. “And then I create a silent movie/You become the star/Is that what you are, dear?”

It was my favourite track when I was 12, and four decades later, I guess it still is. “Come on, let the sun fade and go.”

Finally, since he only gets three originals to Hodgson’s four, Richard Davies is granted a fully solo performance as the prestigious first-side closer: “Downstream” finds him taking a pleasant Sunday boat ride with his new love, relaxed piano keys approximating Satie. A charming song, and a striking way to end the side, following those three near-oppressive thickets of swelling sounds.

Side Two! Roger’s turn again, and he gives us “Babaji,” an anguished spiritual plea to the Indian saint, yogi, and “Sgt. Pepper” cover subject (between William S. Burroughs and Stan Laurel!). Aargh, what can I say, I’ve disliked this track for 40+ years now: Roger Hodgson in maximum-angsty “is it mine is it mine” – whining mode, all doomed minor chords and melodramatic trombone-parps, “Babaji” is the sonic equivalent of a slaughtered calf to my ears…but that’s a highly personal reaction so what do I know? I’m sure it’s someone’s favourite, so shut up.

Anyways, Davies’ “From Now On” begins with a bloozy barroom piano lick that washes the taste of Baba-babble away. It’s a great lick, part boisterous and part hesitant, harmonically indecisive; and it evokes the narrator himself, a bored working-class drone escaping the drudgery of his days through fantasy. “My life is full of romance,” he tells himself, as Helliwell’s saxophone provides the wishful wistfulness; “Guess I’ll rob a [diamond] store, escape the law and live in Italy…” and the music morphs into James Bond-ish exoticism – only to revert to the opening piano again halfway through, no escaping the inevitability of Monday, or the unending monotony of life, as exemplified by a resigned call-and-(imagined?)-response coda that’s seemingly endless.

And finally, we have our big album-closing epic! The 10:52 “Fool’s Overture” (fake sheet music proudly displayed atop the snowy piano in the spectacular cover photo) has a lyric that begins: “History recalls how great the fall can be/While everyone was sleeping, the boats put out to sea,” and ends with “Live it up, rip it up, why so lazy?/Give it out, dish it out, let’s go crazy/YEAH!”; there’s mention of Spider-Man and blue-eyed meanies and even talk of “prophets” and “we’ve many seeds to sow!,” gimme a break!

But the typically overwrought Hodgson vocal/lyric only consumes about three minutes in the middle of the track; and the music surrounding it is quite compelling, exciting even (fast tempos!), ever-shifting and unfolding in organic classical structure. It begins softly, plaintive piano lines doubled by Oberheim synthesizer countermelodies, the piano eventually repeating a descending part again and again unto futility, as musique-concrete fades in and out (Churchill, Big Ben), and a sporadic synth-bass heartbeat begins to pump for real.

Then, suddenly, it’s all huge rushing minor-keyed urgency, in the form of polysynth riff that surely inspired Billy Joel’s “Pressure,” and possibly certain Rush offerings. (And provided the theme music to CTV’s “W5” newsmagazine programme for several years, as Canadians of a certain age will recall.)

It crescendos and resolves into a bit of transitional tastefulness, and Hodgson sings us his words, a careful vocal dripping with significance. Helliwell gives us some more sonic cinematography, his solo saxophone lines battered and blown away by wind FX, as another sound collage swells (this time incorporating Hodgson himself chirping “Dreeeeam-er!”), and again with the synth-heartbeat and huge riff, another shattering climax FOR REAL this time, and it closes to the sounds of an orchestra tuning up. Which is normally done BEFORE the recording session, so: hey, Supertramp close with a joke!

Dean Michaels:

“Ooh yeah!

“Alright…

“Here we go again.”

Even though this series that DJRob, Bloomberg and whatever non de plume I choose to use this month is reposted to my page, this 3 Old Guys thing is basically a regular feature on DJRob’s page.

DJROBBLOG features rock artists regularly, including Supertramp, but his usual focus is on R&B in its various permutations for the most part.

Now I’m not going to deny that, as far as 70’s classic rock goes, Supertramp is absolutely wonder bread – but there’s no reason DJRob shouldn’t love them. It happens to show there is a lot of depth to his love for music. And we all have that including the regular readers of this blog. So with that in mind…

You ever like an album by an artist more than the one by them you realize is the best? I am not talking about cases where there are legitimate debates for their G.O.A.T. such as Prince, P-Funk, Jimi Hendrix or (especially) Stevie Wonder. No, what I am talking about is an album by an artist that you prefer even though you realize they have better releases in their resume.

An example, even if I don’t hold this to be true, would be if you preferred Marvin Gaye’s Let’s Get It On to What’s Goin’ On. There can be different reasons for your preference. Perhaps there is an emotional connection because of a song contained therein or it relates to a certain period in your life. In my case it is usually over exposure to the better album.

Such is the case with Supertramp.

The better album is Breakfast In America. Its over-exposure was due to my mother’s youngest brother who was two years older than me. With a small difference in age we were more like brothers. He was very discerning when it came to the music he enjoyed, and boy he loved that album. The other album he overplayed in that same period was Meatloaf’s Bat Out of Hell. Both albums do hold a special place in my heart because of him; especially after he passed a few years ago.

Now we come to Breakfast in America’s immediate predecessor Even in the Quietest Moments. In a chart year that includes the Eagles’ Hotel California, Bob Seger’s Night Moves, Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours, Steely Dan’s Aja and Rod Stewart’s Footloose and Fancy Free amongst other’s, Supertramp’s entry tends to get overlooked. It is hard to grasp these days how popular Album-Oriented Rock was. At that point Supertramp could be seen as “the little band that could.”

That is until you, depending on your preference, dropped the needle or pushed play on the opening cut. “Give a Little Bit” has one of the most distinctive, beautiful opening guitar figures ever put to tape. The rest of the song does not disappoint. It is my favorite Roger Hodgson cut in the band’s folio. He is the guy with the higher voice. Keyboardist Rick Davies has the lower voice. He usually has a cut to answer Hodgson’s as far as quality is concerned, but not on this album. “Give a Little Bit” stands alone.

Not that Davies’ does not have some good, even great, songs here. The second song on the album, “Lover Boy,” is worthy as is “From Now On.” The fact is though that the second best song on the album also belongs to Rodger Hodgson.

That would be the title cut. “Even in the Quietest Moments” is built on the same beautiful guitar sound that “Give a Little Bit” has. Although sung by Hodgson, the song itself probably fits Davies’ voice more than anything else Hodgson wrote.

The rest of the album explores their soft but prog roots. The concluding cut, “Fool’s Overture,” competes with the Alan Parsons Project as some sort of laidback Pink Floyd proxy. At this point I should mention wind player John Helliwell. His phrasing even in this sort of rock setting is superb and he is used to wonderful effect on the aural canvas. The drummer and bassist are, respectively, Bob C. Benberg (actually Siebenberg) and Dougie Thomson. They are underused here of course, but that is understandable considering the mellowness of the surroundings. I had to look all three of these names up in Wikipedia, by the way. This and Breakfast in America were listened to by me in their original 8-track. Therefore, no liner notes.

Like I said before, I prefer to listen to this rather than their climatic album Breakfast in America. Supertramp’s stock in trade was the Lennon/ McCartney type tradeoff between Hodgson and Davies. That is the reason that Even in the Quietest Moments does not measure up to that monolith.

Hodgson is simply the stronger composer here. The fact that I long ago had too much Breakfast in America should not deter you from listening to it. The truth is I recommend both. As DJRob and my uncle/brother Byron will attest, these two Supertramp albums are addicting!

And that’s each man’s take on Even in the Quietest Moments. Djrobblog gives the sincerest of thanks to my fellow old guys – guest writers Dean Michaels (from Michigan) and Bloomberg (a/k/a Scott Bloomfield, out of Windsor, Ontario) who continue to amaze me with their vast musical tastes and pretty awesome writing skills, too. You can almost hear the music jumping off the page when these two guys write.

Until next month’s installment of the Three Old Guys series, please stay safe!

DJRob

DJRob is a freelance blogger from Chicago who covers R&B, hip-hop, pop and rock genres – plus lots of music news and current stuff! You can follow him on Twitter @djrobblog.

You can also register for free to receive notifications of future articles by visiting the home page (see top for menu).

#blacklivesmatter

[…] Three Old Guys Review Supertramp’s Even in the Quietest Moments […]

[…] Even In the Quietest Moments – Supertramp […]