(January 23, 2020). You might call this the month of Lizzo.

With Grammy night now just days away, and the popular singer/rapper/flautist up for eight awards – more than any other act this year – January could certainly be her month when all is said and done.

Well, actually, it’s really the culmination of a year in which the talented Lizzo, one of 2019’s biggest breakout stars, took America by storm with her in-your-face personality, unapologetically brash live performances (and public appearances), and impressive string of popular hit singles.

Lizzo’s songs “Truth Hurts” and “Good as Hell” ruled the airwaves during the second half of 2019, with “Truth” dominating the Hot 100’s No. 1 spot for seven weeks beginning in September, and “Hell” still riding the top ten as I post this.

It was enough to earn her those eight Grammy nods, including three for “Truth”: Record of the Year, Song of the Year, and Best Pop Solo Performance; as well as Best New Artist and Album of the Year for the deluxe version of Cuz I Love You, to which both “Truth” and “Hell” were added after they became popular.

It goes without saying that America’s fascination with all things Lizzo has been swift and astonishing…well, maybe not so swift considering her most diehard fans have been rocking with her since the middle of the past decade (both “Truth Hurts” and “Good As Hell” were originally released more than two years before they went viral last year). With albums dating back as far as 2015, it’s easy to question why Lizzo would be eligible for a Best New Artist Grammy in 2020.

But she certainly feels new. Since last June, there’s hardly a week that’s gone by where she wasn’t either gracing a magazine cover, dominating social media or simply making news, things that weren’t a thing for her just seven months ago.

She was recently named Time magazine’s “Entertainer of the Year” in a cover feature. She’s also graced the covers of Elle, Entertainment Weekly, Vogue, Billboard and many others in the past six months, with striking cover poses featuring the singer draped in eye-popping ensembles (or no ensembles at all in some cases) befitting the highest-paid supermodels. Each magazine cover photo has been more stunning than the last, with Lizzo exuding sexuality with the ease that a Beyoncé or Kim Kardashian might.

Yet her (delayed) rise to fame hasn’t been without its hiccups. She’s endured accusations of copyright infringement for both “Truth Hurts” and “Juice,” the latter a lower-charting hit from Cuz I Love You that ‘90s singer Ce Ce Peniston thought had a few too many “ya-ya-ees” in it (similar to Peniston’s 1991 hit “Finally”).

On top of that she’s being sued by a delivery service driver whom Lizzo accused of stealing her food (I know, petty BS, right?). And she more recently caught flack for exposing her butt cheeks while twerking at a Lakers basketball game as her song was played over the loudspeakers at Staples Center.

Lizzo, of course, has dismissed the drama and has chalked much of it up to haters being haters. Contrary to some who believe that her over-the-top antics reflect a suppressed level of insecurity, she’s maintained that what we’re getting is real, and it reflects a newfound self-love that she didn’t always have, particularly given her struggles with her weight in the past.

Her past struggles are what fuels her now, she’s admitted, and they compel her to deliver messages of unconditional self-love as loudly and proudly as she can to anyone who will listen…especially to those who look like her – full-figured, black and female – who might also benefit from it.

It is that last part that is especially significant when considering the social backdrop of American history and the way black women have been portrayed throughout it, particularly our full-figured sisters who have only in the past century emerged from some of the most unflattering imagery any demographic has had to endure in this country.

It wasn’t that long ago that black women here were coded exclusively as overweight (whether they were or not), sexless, caretaker types whose lot in life was to happily serve others…usually the white families for whom they worked.

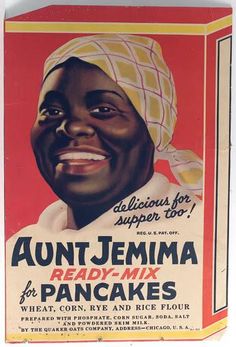

It was nothing to see the exaggerated image of the heavy black woman – usually with dark, dewey skin and contrasting pearly white teeth flashing a great big smile – gracing the packages of food products, coffee, soaps and other domesticities.

The mascot for the most famous pancake brand – Aunt Jemima – was created, for example, as a “mammy” character, and only in the past 30 years doffed the do-rag and took on less exaggerated features in the product’s current packaging and in ads. Correspondingly, the Mrs. Butterworth’s syrup container is a silhouette of a “mammy” character that remains to this day.

In film, the big black woman was literally a “mammy,” the character that embodied the fantasy of white film producers and directors who believed – or wanted audiences to believe – that uneducated, sassy-mouthed, but dutiful nonetheless, servants were all that black women could or should aspire to be.

In the classic 1939 film Gone With the Wind, actress Hattie McDaniel portrayed a character actually named “Mammy,” a role for which she became the first black actor to win an Oscar (Best Supporting Actress) in 1940. At the time, McDaniel, who had made a career of playing mammy types, rebuked her critics – namely progressive thinkers in the black community – by famously remarking, “Why should I complain about making seven thousand dollars a week playing a maid? If I didn’t, I’d be making seven dollars a week actually being one.”

Despite her place in history, McDaniel didn’t have the mammy market cornered. The epitome of the caricature occurred in the 1934 film The Imitation of Life, in which actress Louise Beavers played the black, live-in maid Aunt Delilah. In the film, she inherits – of all things – a pancake recipe and stands to gain a profit on its sales, which would allow her to move on to her own home with her own car, free from her life as a servant.

Instead, the frightened Aunt Delilah cries, “My own house? You gonna send me away, Miss Bea? I can’t live with you? Oh, Honey Chile, please don’t send me away.”

She finishes, “How I gonna take care of you and Miss Jessie (Miss Bea’s daughter) if I ain’t here… I’se your cook. And I want to stay your cook.”

Beavers also notoriously had a weight problem – that of trying to keep the extra pounds ON in order to continue playing the mammy archetype.

Her most famous role was reprised in the 1959 remake of Imitation by actress Juanita Moore, who became only the fifth black actor to be nominated for an Academy Award (also for Best Supporting Actress) for her role as Aunt Delilah.

These mascots and portrayals were indeed intentional. They catered to a white audience while sending messages to the black one. To white people, the image of Aunt Jemima was that of a loving black servant willingly putting warm food on your plate, whereas to black folks the message from the smiling, do-rag-wearing, overweight woman was clear: your future is as a domestic servant, so get used to it.

So what flipped the script? For the full-figured black woman in particular, when did she go from Mammy to Lizzo – from the happy, sexless, compliant servant, to the happy, curve-embracing, defiant diva?

When did she go from being the most demeaned figure in American popular culture to the most celebrated entertainer of the moment?

It’s taken decades of activism, particularly by black women in entertainment, to change the course of history. First, women whose images contradicted the stereotypes were given chances in Hollywood. Actresses like Dorothy Dandridge and Diahann Carroll – fair-skinned and skinny but black, nonetheless – broke color barriers with their roles and award-worthy performances.

In music, images of skinnier black women became prevalent in the mid-to-late 20th century with the likes of Motown greats like Mary Wells, Martha Reeves, and Diana Ross & the Supremes crossing over to mainstream audiences. Other pop singers like Dionne Warwick and Marilyn McCoo showed that black women were just as comfortable with pop standards as they were with the jazz and blues that had characterized earlier stars.

But even with those women’s success, their bigger, darker complexioned counterparts were still being pigeonholed into stereotypes. It took further action to rebuke those roles as the decades progressed.

In the 1970s, for instance, the late actress Esther Rolle famously knocked down at least one stereotype when she demanded that her character Florida (on TV’s Good Times) have children AND a husband at home, despite the fact that Florida had been introduced as a maid for a white family in the sitcom Maude a few years earlier (and despite the fact that her “nuclear family” with a working husband lived in government projects).

Yet the notion that Florida could be a stay-at-home mother who cared for her own kids – and not those of a white family she served – was a big deal to black people in the late 20th century (and Good Times regularly placed in the Nielsen top 10 during its heyday, which meant some white folks were watching, too).

But bigger black women being portrayed as sexy, desirable entities still wasn’t a thing yet. They were still single moms (Theresa Merritt in ‘70s sitcom That’s My Mama), live-in maids and surrogate mothers to other (white) people’s children (Nell Carter in ‘80s sitcom Gimme a Break), or otherwise generally non-existent.

In the music world, the late Aretha Franklin, who struggled with her weight throughout her career, was perhaps the greatest singer of all time, but her lone movie role was as the slipper wearing, grease-stained apron-donning owner of a soul food restaurant in the classic 1980 movie Blues Brothers (her performance of “Think” with the late Matt “Guitar” Murphey was still iconic, though).

Singers like Jennifer Holliday and Martha Wash weren’t viewed or portrayed as sex symbols. In fact, Martha was famously replaced in music videos by a skinnier model for songs she recorded for the group C&C Music Factory in 1990.

It wasn’t until the late ‘80s and throughout the 1990s that society began to see fuller-sized black women in a broader context on a more regular basis. Entertainers like Oprah Winfrey, Queen Latifah, Kim Coles, Jill Scott, Jennifer Hudson and Mo’Nique – among others – brought more color and personality to either the characters they played in film or the songs they sang or rapped to.

By the late 1990s, rapper Missy Elliott had shown the kind of tripped-out, ahead-of-her-time, futuristic vibe that had been reserved for skinny white chicks like Annie Lennox and Bjork. As years went by, Missy would explore her sexuality even more by incorporating provocative lyrics in her verses.

And the unapologetic big girl swag that Lizzo exudes onstage today was famously delivered by Mo’Nique fifteen years earlier in the opening number of the 2004 BET Awards. It was in a tribute to Beyoncé where Mo’Nique and several other plus-sized women danced in a sexily choreographed number – just like video vixens – to Bey’s “Crazy in Love.”

It was Mo’Nique’s way of saying, “I’m big, I’m black, and I’m sexy as hell. Get used to it!” Indeed, Mo had the BET audience, which included a “shook” Beyoncé, totally captivated…mainly because the world hadn’t seen anything like it before then and, for a long time, since.

And now Lizzo, who is achieving success and recognition on a level that few of the above-mentioned women before her ever did, is the latest big girl with swag. Her success, which is largely fueled by the sexuality she fully exudes and embraces – curves and all – has redefined how the plus-sized black woman is seen not only in entertainment, but in society as a whole.

Some of us may not appreciate her more audacious performances and consider them tactless and ill-advised, especially for someone who likely wants people to take her seriously – even if she doesn’t always do so herself.

But it doesn’t really matter what we think, does it?

Lizzo, whether driven by self-consciousness or self-confidence, is rejecting society’s pressure to fit a certain mold. She’s basically living her own truth, even if that includes twerking in public while playing her flute. And that attitude more than anything may be why she’s the entertainment world’s darling in 2020.

In a sense, as Lizzo told Great Big Story in a 2017 interview, her mere existence as a musician is activism.

And you know what? Given how far the plus-sized black woman has had to come in American entertainment over the past 150 years, Lizzo may be exactly right.

And we may all be the better for it.

DJRob

DJRob is a freelance blogger who covers R&B, hip-hop, pop and rock genres – plus lots of music news and current stuff! You can follow him on Twitter @djrobblog.

You can also register for free to receive notifications of future articles by visiting the home page (see top for menu).

Kelly Price was the epitome of BBW in the late 90s

Last year it was Lil Nas X, this year it’s Lizzo. Who will be exploited next? Young gay black boys, or fat black women? Either way the stereotypes are coming back to life in a big way. Mammy, coon, buck, and sapphire have all been played up close and out front. What’s worse is millennials don’t seem to care. The cultural connection to Jim Crow, minstrels, and the aftermath of slavery has all but disappeared. The schools and text books barely educate a generation, and even worse, some of us (parents, teachers, aka Black People) have acquired selective amnesia. So, we are reactionary when someone is beaten or killed publicly. We are numb to the constant humiliation of our race. Yes!, I am Black af. Heaven help us all. The agendas are real. I’m waiting for Jim Crow to exhale…?. Lizzo, is a marginalized large black woman, but aren’t we all? I’m 100% that bitch ?too. ?♂️ Smh

Los, they were BOTH last year. They’re both up for Grammys for what they did in 2019. The article speaks of how women have evolved from Mammy caricatures – NOT how Lizzo is being treated as one.