(July 15, 2024). You never know when or how your emotions might be triggered, or from what you might draw inspiration to write about the experience in a blog post. I began writing this article days before this past Saturday’s events, in which political violence reared its head once again during an attempt on Donald Trump’s life (July 13, 2024). I completed it today.

The inspiration for this article occurred last Sunday (July 7) as my mom and I were returning home from a Maryland trip to visit my sister and her family for the July 4th holiday. On the way back, we stopped and visited my dad’s grave at Arlington National Cemetery. It was extremely hot that day, but we made it a point to spend as much time with him as we could, noting that a woman about 30 yards from us was enduring the unbearable heat with a lawn chair and reading material – along with several small gift items – to spend even longer with her dearly departed than we had intended with Dad.

The visit went as expected. We drove around ANC’s vast maze of roads leading to and from the various sections of neatly arranged graves reserved for the military’s fallen and others deemed worthy by the U.S. government. We paid our respects to my father as we had on several other occasions. Then we left for the two-and-a-half-hour trek back to Central Virginia. My mother might have shed a tear or two while at the gravesite, but I’d remained stoic…even finding room for levity in response to my mom’s quips to my dad about how “badly” I had been behaving, which was typical banter between Mom and me.

On the long drive back home, we listened to a Spotify playlist of songs curated by a good friend of mine (Spotify handle: ramsees48). It was one of many year-based countdowns he’d created containing greatest hits from the 1960s, ‘70s and ‘80s – this one being focused on 1971. It was about 30 minutes in, when it played a tune by a once-popular DJ named Tom Clay, that I lost it.

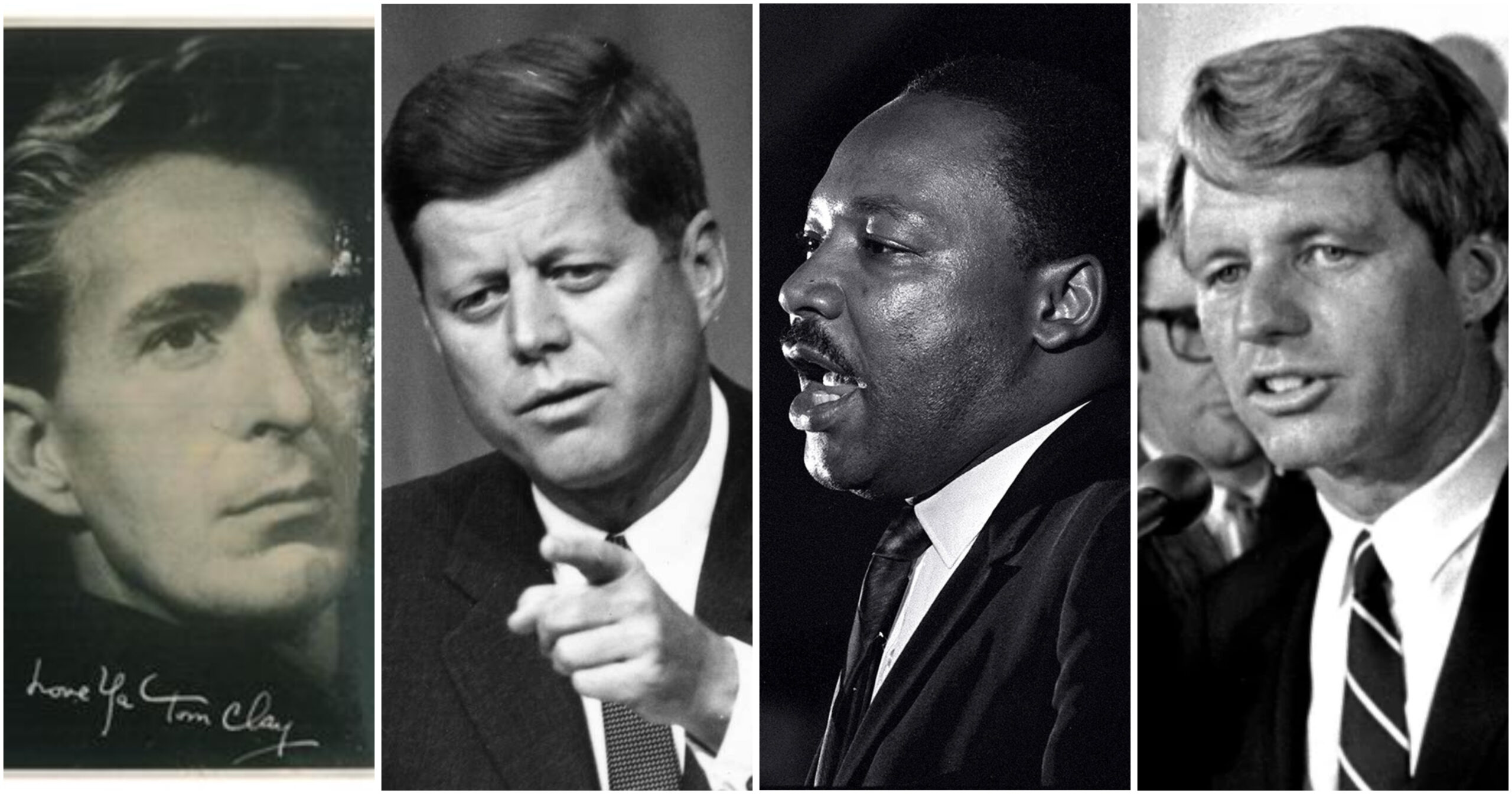

The song was a medley of “What the World Needs Now Is Love” (written by Burt Bacharach and Hal David) and “Abraham, Martin, and John” (penned by Dick Holler), not the original hit versions of those tunes from the 1960s recorded by Jackie DeShannon and Dion, respectively, but a medley sung by a group of unknown studio vocalists called the Blackberries who’d been rounded up by Clay, a former Detroit DJ who recorded the song in L.A.

In fact, Clay was signed to Motown’s new subsidiary label at the time – MoWest – a short-lived venture created by Berry Gordy to market the west-coast sound that the newly relocated corporation was experimenting with following its own move from Detroit to Los Angeles a year or so earlier.

Clay’s “What the World Needs Now Is Love/ Abraham, Martin and John” would become MoWest’s only hit. It was an admittedly cheesy production featuring a syrupy collage of the two songs interspersed with historical soundbites from the turbulent 1960s, namely the assassinations of President John F. Kennedy, the reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and former Senator and presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy. Those three social and political icons, along with President Abraham Lincoln, had been the subjects of the original “Abraham, Martin and John.”

But the song’s first vignette featured a man, presumably Clay, interviewing small children and asking if they knew what “segregation,” “bigotry,” “hatred,” and “prejudice” meant. The kids, in their replies, couldn’t even pronounce the words, much less define them. Yet the song’s intended message was already perfectly clear, especially when the last child interviewed equated the word “prejudice” to being “sick.”

The song then segued into the sound of soldiers marching under a platoon sergeant’s call-and-response cadence while military gunfire erupted around them. As the soldiers began chanting under their leader’s command, the tears immediately began welling up as I imagined my father’s time in the military – particularly his 1968-69 deployment to Vietnam during the war – which culminated in his being buried at Arlington, where we’d just departed minutes earlier.

It wasn’t like I hadn’t heard this tune previously… I had, several times, particularly on reruns of old “American Top 40” countdowns with Casey Kasem. Like the two songs that inspired it individually had, the medley of “What the World Needs Now Is Love/ Abraham, Martin and John” also reached the top 10, peaking at No. 8 in August 1971 and selling a million copies.

Motown’s MoWest label never duplicated that success and, for that matter, neither did Tom Clay, who’d previously bounced between radios stations while dodging legal issues brought on by fraudulent scams he’d allegedly spearheaded. He and Motown parted ways shortly after “What the World Needs Now/Abraham, Martin and John,” and Motown dissolved the MoWest imprint less than two years after it was launched. Clay died in 1995 at the age of 66.

My familiarity with some of this history, and most importantly with the song itself, should have prepared me emotionally for what was to come, or so I thought. But hearing that military cadence connected me to Clay’s record – and to my father and the turbulent ‘60s – in ways that it hadn’t previously, no doubt triggered by the day’s visit to Arlington. The tears, which I tried to conceal from my mother who was seated next to me as we drove down I-95, just came.

Thank goodness I was wearing dark shades so at least the redness of my eyes wouldn’t be visible. I thought for a moment that maybe this would all stop once the song moved past the soldiers marching and into the other soundbites.

It didn’t. The tears were relentless.

As the song reached snippets of the fateful JFK motorcade in November 1963, plus excerpts of Dr. King’s final speech (“I’ve Been to the Mountaintop”) and later, that of Bobby Kennedy’s last campaign stop, the tears kept flowing. As someone who had just turned two when the last man was killed, I certainly didn’t remember any of these events. Yet, the weight of this history was suddenly too much.

Both King and Bobby Kennedy had been opposed to the Vietnam War. King’s assassination that April came just a day after his “Mountaintop” speech, during which he denounced war and violence, and exactly one month before my dad’s deployment to this foreign land.

In his final campaign speech, Bobby’s last words — as captured in the song — were “it’s on to Chicago and let’s win there.” That year’s Democratic National Convention was held in the Windy City that August — nearly three months after Kennedy’s death — and would be marred by rioting and protests of a divided party…mainly over the ongoing war my dad was actively fighting. All of these thoughts were swirling around in my head as the tears streamed down my face.

At this point during our drive, my mother – upon hearing this unusual song medley – began recalling how she’d lived through these tragedies, beginning with the first Kennedy assassination, which preceded my birth by nearly three years. Knowing any response would reveal my still-emotional state, I remained silent. The silence must have prompted her to look over and see the mess I was slowly becoming – the dark glasses no longer able to conceal the tears trickling down my right cheek – and she rubbed my right arm, which was resting on the center console, as if to comfort me. Without asking, she knew that the song or our earlier visit to Arlington – or both – had moved me to tears.

I then tried to explain my emotions by stating “this song gets me every time,” or something equally dismissive. Why did I feel the need to do that? Surely, any tune denouncing bigotry and recalling the assassinations of three of America’s greatest leaders, along with the sound of soldiers not unlike my late father marching off to war, warranted an emotional reaction. The quavering voice of the late Sen. Ted Kennedy, whose 1968 eulogy of his slain brother Bobby was included as the song’s last historical soundbite, was even tougher to bear. I certainly would have mimicked his voice had I attempted to speak any further. Only the termination of the song – whose six minutes and 15 seconds seemingly took forever – would shut off the flow from my now saturated tear ducts.

The 1960s were indeed a tumultuous time, a decade in which the events depicted in Clay’s tune would change the course of history forever. Perhaps it was the weight of that history that got to me. Maybe it was knowing that my father fought in the very war that was at the center of much of that turmoil, and that he’d paid the ultimate price with his exposure to the chemical agent to which his terminal cancer diagnosis was later linked, that made this song more emotionally challenging than it had been previously.

Or maybe it was my simply having just seen the graves of my dad and other soldiers buried at Arlington National Cemetery, a site that had been established for that purpose a century before the Vietnam War (in the 1860s). The connections between the cemetery’s history and significant mileposts in my immediate family were indeed noteworthy, if not uncanny.

The land on which the cemetery sits was once owned by the family of Confederate general Robert E. Lee, whose own memorial still rests on the property. It was my dad’s 1976 assignment to Fort Lee — named for the general but since changed to Fort Gregg-Adams as part of the military base renamings in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement of the early 2020s — that led to our family’s permanent settlement in Virginia.

General Lee’s wife, Mary Anna Custis Lee, who’d won a Supreme Court judgment against the federal government after the Union seized her home — Arlington House — and its vast acreage in a nefarious tax sale, regained ownership of the property late in the Civil War and resold it to the government on March 3, 1864. March 3 happened to be the day of my younger brother’s birth 104 years later, two months before my father was deployed to Vietnam.

Arlington National Cemetery became the country’s official military burial ground on June 15, 1864, one day removed from what would be my birth date 102 years later. The cemetery’s current superintendent, Charles R. Alexander, was appointed to his position on February 18, 2020, just days before my father – whose first two names were also Charles Alexander – passed away.

My dad is buried in an area of the cemetery’s 21st century expansion known as the Millenium Project. As many as a hundred people or more are buried at ANC every week, with roughly 6,000 interred at the cemetery each year. My dad’s grave is already joined by hundreds of others in the section that had just been opened less than a year prior to his burial. The three Kennedy brothers — John F., Robert F., and Ted — are buried in plots at this same cemetery.

But those facts – and all the interconnected history they embodied – were tangential to the musical moment that brought me to tears upon hearing this time capsule that was Clay’s “What the World Needs Now Is Love/Abraham, Martin and John,” a tune I’d heard many times before but for unexpected reasons created extreme waterworks on Sunday, July 7, 2024, as I returned home from Arlington.

As I listened to the song again while writing this article, to ensure that I had the finer details accurately depicted, tears welled up again. Maybe it’s just that the song, as cheesy an amalgamation of events as it may seem, is really that good.

DJRob

Ps. This article was initially drafted days before the recent events involving an attempt on former president and current Republican candidate Donald Trump’s life (July 13, 2024). But the historical context is not lost on this blogger, nor is that of the upcoming Democratic National Convention being held in Chicago this year for only the second time since 1968, particularly with the country as politically and ideologically divided as it has ever been. Yes, things are different today than they were 56 years ago… but the more things change, the more they stay the same.

DJRob (he/him) is a freelance music blogger from the East Coast who covers R&B, hip-hop, disco, pop, rock and country genres – plus lots of music news and current stuff! You can follow him on X (formerly Twitter) at @djrobblog and on Meta’s Threads.

You can also register for free (select the menu bars above) to receive notifications of future articles.